<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

Remembering Vitas

By Trey Waltke with Joel Drucker

Timing can be both a blessing and a curse. During my entire career as a tennis player, from

the juniors all the way into the pros, it was the fate of

dozens of my contemporaries to play in the shadow of another generation. I was born in 1955, and along with the likes of Brian

Teacher, Bill Scanlon, Gene Mayer and many others a year or two older and younger than

me, we were three-four years younger than one of the greatest crops of Americans in history – the likes of Jimmy Connors, Roscoe Tanner, Sandy Mayer, Harold Solomon,

Eddie Dibbs, Dick Stockton and Brian Gottfried. It was rough. When we were 16, these

guys were already tuning up for college tennis. When we turned pro, they were already

experienced veterans. And when we entered our prime, they were pretty much in the thick of

theirs too.

Timing can be both a blessing and a curse. During my entire career as a tennis player, from

the juniors all the way into the pros, it was the fate of

dozens of my contemporaries to play in the shadow of another generation. I was born in 1955, and along with the likes of Brian

Teacher, Bill Scanlon, Gene Mayer and many others a year or two older and younger than

me, we were three-four years younger than one of the greatest crops of Americans in history – the likes of Jimmy Connors, Roscoe Tanner, Sandy Mayer, Harold Solomon,

Eddie Dibbs, Dick Stockton and Brian Gottfried. It was rough. When we were 16, these

guys were already tuning up for college tennis. When we turned pro, they were already

experienced veterans. And when we entered our prime, they were pretty much in the thick of

theirs too.

I say this as a prologue to a personal memoir of the one member of our generation who most vividly leapfrogged his way out of our collective inferiority complex: Vitas Gerulaitis. It’s hard to believe it’s been six years since Vitas died tragically of carbon monoxide poisoning at 40.

While he doesn’t carry quite the same weight on the tennis stock exchange as a Borg, Connors or McEnroe, the truth is that for a short, lively period in the late ‘70s, only those three geniuses were consistently better than Vitas. His resume featured numerous impressive results: finalist at both Roland Garros and the U.S. Open, twice in the semis at Wimbledon, twice a victor at the Italian (more on this later), Australian Open champ, once the winner of the prestigious WCT Dallas tournament, twice runner-up at the season-ending Masters.

Perhaps to the public, Vitas was perceived as not quite as good as the Borg-Connors-McEnroe troika, and arguably a shade off of Guillermo Vilas. But the view from the player’s vantage point is quite different. Again, outside of those three, Vitas at his best stood at the top of a long list of impressive players.

Of the older American generation, only Connors dominated him – though in a typically Vitas manner, after he’d ended a 16-match losing streak to Connors, he issued a quote that revealed both his tenacity and charm: “Nobody beats Vitas Gerulaitis 17 times in a row.” Proving it was no fluke, he won his next three matches over Connors, including an impressive semi at Roland Garros from two sets to one down. And among foreigners, Vitas vanquished a whole slew of rivals – artful Raul Ramirez, the talented (albeit fading) Ilie Nastase, crafty Manolo Orantes and even, with trademark moxie, such rough customers as Vilas and Ivan Lendl.

But even more than his resume, I want to give you a sense of what made Vitas a special person, based on my experiences hearing about him as a junior and, later, becoming part of his circle of friends and practice partners.

|

|

|

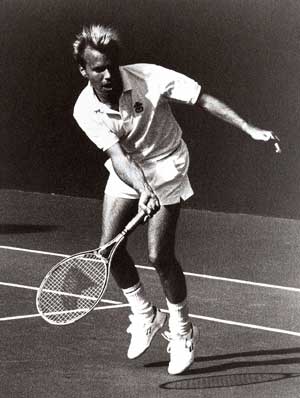

During Vitas' heyday, only McEnroe, Connors, and Borg could consistently beat him. |

||

From the minute you met him, you could tell Vitas Gerulaitis was born with natural charisma and a self-confidence that enabled him to never question his place in tennis greatness. In the early ‘70s, while I was growing up in St. Louis, I remember hearing from some of the top Eastern juniors that there was this guy "Vitas" from N.Y. who was so ambitious that he didn't care if he got a good junior ranking. A year older than me, Vitas was supposedly practicing with such top American men as Clark Graebner, Gene Scott, Chuck McKinley and Ron Holmberg. All of these guys had been in the big time, playing Davis Cup, Slam semis and finals – and Vitas, all of 17, was actually beating them.

This obviously scared all us juniors into thinking this Vitas character was already better than the rest of us. Vitas first surfaced at Kalamazoo when he was 17. Even though he lost to 'big Vic' Amaya, a powerful, tall lefty from Michigan who looked more like a defensive end than a tennis player, the buzz around the event was that this Vitas guy had the whole crowd roaring with laughter the whole match. It was an incredible sight for a teenager like me to see. Here was the first junior I ever saw or heard about who could work a crowd.

Shortly after that, no matter if he was winning or losing, everyone was drawn to Vitas’ magnetism. He was from the same part of Queen’s as the popular DJ, Howard Stern. The two are uncannily similar: same age, same rangy size, same look, same quick-witted, street-smart banter with that New York accent just kind of getting in your face with a smile. But while Stern’s got black hair, Vitas had those flowing blonde locks that made him the quintessential ‘70s icon. Juniors were blown away when they saw him walk out of his yellow Datsun 240 Z.

|

Everything Vitas did seemed bigger than life and more dynamic than anyone else. If he practiced, he practiced for six hours. If he went out, it was until 6 in the morning. If he ate dinner, it was with 15 people.

You haven't shopped until you've shopped with Vitas. I'll never forget going with Vitas to Sam Goody’s, a New York record store. I was from the Midwest, a careful shopper who would spend a long time considering which solitary album I would buy. Not Vitas. He would ask someone who worked there to grab a big basket or two and follow him while he walked up and down the aisles, pointing to records he wanted and in the quantities he wanted. When it was over, there were at least 200 albums in the baskets. This kind of thing happened all the time. And you knew Vitas wasn’t planning to hoard the albums, but to give them to folks like his sister, Ruta, or one of his many girlfriends, or even to his playing rivals like McEnroe (who was five years younger and had looked up to Vitas when they were both coming up at Port Washington Tennis Academy).

You see, while those other three taught us all a great deal about how to play tennis, Vitas was teaching them – and us – how to live life: with passion and perspective. Somehow, while everyone (including Vitas) was getting all worked up about winning matches, Vitas knew tennis was also this great amusement park where you should make sure to enjoy every ride. And he wanted to share in that joy with as many people as possible. His generosity wasn’t confined to food and music. One year, he arranged for Tony Giammalva and myself to practice with him for a series of Italian tournaments. We were making less than Vitas. Without making a deal of it, he covered every bill.

And don’t be fooled. Vitas played hard, but he worked even harder. He could easily and frequently drill for a couple of hours, play six sets and work on his conditioning in the same day. I remember tuning him up for Borg with a couple of sets, then transitioning into his pool while Vitas and Bjorn went after each other for another three hours.

By 1976, it was obvious Vitas was destined to be at least a top five player. Everyone felt it and he was sure of it. I remember Bob Kain (his IMG agent who also handled Borg) saying that if Vitas won Wimbledon, he'd bigger than Joe Namath. Vitas clearly saw himself on the same plane as Borg and Connors, and shrewdly made every effort to become their buddies, not just as practice partners but also so he could learn and work with the very best.

|

Vitas's coach at the time was Australian legend Harry Hopman. I think it was Vitas's goal to hear Mr. Hopman say that none of his players ever worked as hard or as long day after day. In contrast to how he used to argue with his father (also a tennis teacher) regarding his tennis, Vitas never questioned anything Mr. Hopman said. We’d show up on the court and “Hop” would just start firing ball after ball into corners. Vitas covered every one like a fox terrier. “Hop” was the only person I ever saw Vitas totally respect.

What made Vitas so tough was his speed and tenacity. He was always moving forward, always looking to take charge of a point by getting his way into the net and force you to try the difficult pass. This was the way many Americans in the ‘50s and ‘60s had learned to play – Jack Kramer’s “Big Game” of serve-volley, chip-charge and the application of cumulative pressure.

Again, for a time, only such geniuses as the topspinning Borg, hard-driving Connors and artistic McEnroe could outplay Vitas. At 6’-1”, he was rangy, fit and could do a good job hanging from the baseline while waiting for his opportunity. His forehand was solid and powerful, his backhand slice approach was superb. When forced to play defense, he was smart about not overplaying his passing shots and judiciously lobbing. And once he took the offense, so many of us – smaller, less quick versions of Vitas – felt smothered.

Interestingly enough, for a net-rusher, Vitas had outstanding results at the Italian Open. One reason for this was that Vitas was the Pied Piper of Rome. I always thought Vitas and Italy had a mutual love affair. The festive lifestyle and Vitas' flamboyance, combined with the Tacchini clothing contracts a number of us had, all melded perfectly. While the rest of us took Alfa Romeo transportation cars, Vitas zipped around Rome in a Ferrari, courtesy of the tournament committee. Every night we'd have dinner at one of Rome's finest restaurants while taking anyone we happened to run into with us. Vitas never let anyone pay.

It was as if Vitas wanted to be the Roy Emerson of the Open era – hard work, fun times and, in these days, increasing amounts of prize money that was worth sharing, spending and enjoying. Vitas was the first tennis player of the Open era who forged a bridge to pop culture, befriending the Studio 54 culture of Andy Warhol, Mick and Bianca Jagger, David Bowie and more. But as much as Vitas liked dancing, his feet put in even more time on the practice court. Never was Vitas’ work ethic more vivid than at the ’79 Italian, when he won a five-hour match from Guillermo Vilas on a roasting red clay court. The score of the first four sets – 6-7, 7-6, 6-7, 6-4 – shows just how close it was and how much effort it took for Vitas to keep pressing ahead. Since there was no way he could beat the bull-like Argentine from the baseline, Vitas came in like there was no tomorrow. This was pretty courageous given what a bull Vilas was – his topspin drives could leave you weary and you’d be forced to deal with one dipper after another when you came in. But Vitas lived for these toe-to-toe moments. From 2-all in the fifth, he won four straight games.

|

Oddly enough, though, even that great Italian win took place after Vitas’ peak. To me, Vitas

played the best tennis he could play when he lost to Borg in the semis of Wimbledon ‘77. All

of us players felt it was Vitas' turn. He’d vaulted into the top ten and was now beating Borg a

lot in practice and he just seemed to have the perfect momentum heading into that match. It almost happened. Borg and Vitas knew each other’s games so well it was like watching ballet. As always, Vitas continually attacked, knifing approach shots, striking volleys, leaping

for overheads. Borg countered, running down shots from seemingly unreachable corners.

Despite serving at 3-2 in the fifth, Vitas couldn’t quite get there, losing that final set, 8-6.

An odd thing happened in the wake of that match. Though Vitas was still great, and would

spend another five years in the top ten, it was clear he’d hit his glass ceiling, and instead of

rocketing through and becoming one of “them” – a Connors or Borg who wore the aura of a

big-time champ – he was now simply one of “us” – a guy who seemed beatable.

I believe deep down Vitas sensed he had played the best he could play, and if that wasn’t good enough, he was just going to have to settle for what he could get. And complacency is dangerous. Tennis is ruthless this way. The aura is either being built up or being taken down. I think the other players felt it too. On a pure mechanical basis, I think if Vitas’ serve had been just a little more intimidating, he would have won a Wimbledon or U.S. Open or two. But even while he could in time score wins over Connors, he never did beat Borg in a tournament match.

When Vitas retired, I sensed he went into his own version of the decompression period – that time when an ex-player realizes he’s lived a full life playing, but most now face the rest of his life. As fun as it was to hang around his infectious energy, I always felt he was happier being ringleader of a group, and felt particularly enthused about this when he was an elite player. During his glory years, Vitas rarely would be around just one person. But later, even while still playing, he did just the opposite. He would spend many hours alone with his guitar as if it was the only thing he could now trust. Many people were around the entourage when he was winning. Now for the first time he was learning to be by himself.

I heard about Vitas's death on television. All of us who hadn't spoken in years called each other in disbelief. What struck me as ironic was that Vitas was bringing us all together again in his death just as he had in his life. The day after Vitas’ funeral, for example, the New York Times ran a photo of Connors and McEnroe hugging. Only Vitas could have made that happen. Those of us who had the privilege to have our lives intersect with this person all feel a private smile in our hearts when someone mentions the name Vitas.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think by emailing us here at TennisONE.

Last Updated 4/1/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.