In his prime he was one of the best of all time. But for the last

few years, except for a few epic performances, the magic seems to be

gone.

|

Hitting the ball early is definitely a concept that

needs closer examination. Even at the highest levels I have seen players

lose their superb timing and touch just by setting up too early.

Take Pete Sampras, for example. In his prime he was,

along with Rod Laver, one of the best players of all time. But for the

last few years, except for a few epic performances, the magic seems to be

gone from his racquet. Could the explanation be something as simple as

preparing his groundstrokes much earlier than before? Is this what is

contributing to his uncharacteristic unforced errors?

When players get older they are usually counseled to

take the racquet back earlier to compensate for slower reaction time.

Chris Evert followed that path, so did Guillermo Vilas, Gabi Sabatini and

many other champions, and soon their best game was lost.

The reason is very simple. The player who used to

react naturally, in a totally instinctive way, is now using a mechanical

compensation to counter balance a natural phenomena, the slowing down with

age.

Stalking the Ball

Great groundstrokers stalk the ball as it is coming

in, following it with their racquets out front, pointing at the ball.

Their attention is absorbed in the moment - in adjusting to the ballís

path. Then, in what seems like the nick of time, they stroke it

smoothly, confidently, and with uncanny accuracy.

By setting up the stroke too early, the player must

imagine the ballís path prior to the actual trajectory happening. In other

words the player must make adjustments to where he thinks the ball will be

instead of the actual path of the ball.

More importantly, by setting up too early, there is a

span of time where a player's mind can wander, call it daydreaming if

you like and this distracts from focusing exclusively on the path of the

incoming ball. All this may occur in hundredths of a second, but it is

still a distractive additive that need not be there.

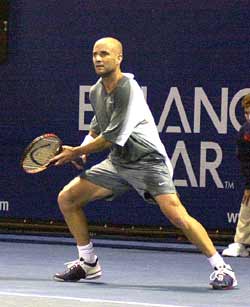

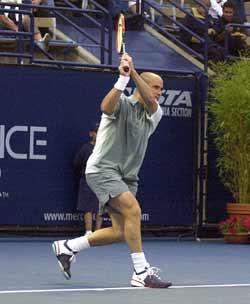

Notice how Agassi stalks the ball as it is coming, following it

with his racquet in front, pointing at the ball.

|

This happened to Bjorn Borg when

I was coaching him during his second comeback attempt. I noticed he was

preparing earlier than usual for his shots, rushing them in fact. I

suggested he wait longer on the ball. "The more you wait, the more time

you will have,Ē I said.

By tracking the ball longer, Borg narrowed his focus

on the one immediate task instead of concentrating on extraneous

distractions and the work paid off for him allowing him to regain some of

his lost form. Just 20 days later, he had a wonderful practice match with

Pete Sampras, losing a close 7/5 7/6. Afterward, he told me he felt as if

he had so much time now.

This takes us right to my opening statement. Hitting

early is a concept that needs closer examination. It's one thing to

move inside the court shortening your opponent's response time. There

are many players, Agassi being the prime example, who like to attack the

ball on groundstrokes, hugging the baseline or even prowling further

inside the court. But

Agassi is not rushing his preparation.

Keep your eyes fixed on him during the setup and

stroke, rather than looking at the ball he is playing. Notice how long he

stalks the ball, keeping the racquet in both hands towards the front.

Almost as if he was pointing to the ball with the racquet.

Sampras, in his prime,

also exhibited this trait, most noticeably on the forehand side -

pointing to the ball with his racquet for a long time. That seems to have

changed. At the high speeds of professional tennis, if a player

executes just a few hundredths of a second too early, the brilliance of

his game can be lost. Errors creep in yet

the player doesn't know what is going on. His fabulous touch is gone,

along with that wonderful sensation that he can do no wrong.

Setting up too Early

For heavy topspin players, being slightly early makes it more difficult

to lift the ball to their liking. They have to hit much more in front of

their bodies, and they lose their force.

Agassi sets up inside the baseline robbing his opponent of

response time but he does not rush his preparation.

|

At the highest level of the game it is hard to detect

when a player is preparing earlier, but the shots seem a bit weaker, the

ball has less sting, and the once uncanny accuracy is no longer sharp. The

sting or weight of a shot does not depend on the speed of the racquet

head, but rather on the acceleration and weight applied at impact.

Todayís champions allow their racquets to approach

the ball slowly, then, only at the last possible moment, they release

their sting. This gives the ball more energy and more bite. If you

approach the ball slowly, almost touching it, and then increase

acceleration, you will feel the contact on your strings for a longer

period. The ball will then take off at a high speed as if it were shot

from your racquet.

Your eyes may not notice it, but you will feel the

difference - a sensation more solid, a bit longer, and with much more

control. Practice this and you will be less likely to experience sudden

loss of control, where the ball flies off your racquet even though you

were actually trying to gain more control by

restraining your power.

The speed of the ball, even when applying the same

amount of force, depends on how close to the contact point you start

applying that force. If you release your power early, too far from the

ball, as a baseball batter might, you're likely to get a lot of ball speed,

but very little control.

So here is where the real balance occurs in tennis

and that balance is literally

in your hands. You control it by timing the release of your power,

choosing carefully the point where you exercise your strength. You don't

have to hold back the force, but you must release it at precisely the

right time.

Here Agassi stalks the ball with his racquet forward, his

attention is absorbed in the moment - in adjusting to the ballís path.

|

If a top professional persists on hitting the ball

earlier than usual, not noticing that he or she is a few hundredths of a

second ahead on his optimum release, or that the court plays a bit slower

than the one he has practiced on, he starts to lose his confidence. He may

become a bit tense, not really feeling the ball, his "touch" gone,

confusion abounds.

This happens more frequently to players who like to

strike groundstrokes early. They are playing with fire, too close to the

"too early" frontier. But there are the geniuses out there. Who, on their

best days, display the magic, the talent in full flight. They seem to

just touch the ball and it strikes like lightning. This has been Andre Agassi's brilliance over the years. He stokes the fire, he plays with it,

but he rarely gets burned.

What he learned early in his career, perhaps aided by

McEnroe's famous 1992 tip a few weeks before Agassi's first Grand

Slam victory at

Wimbledon, "On grass courts, no backswing," was to wait longer

with the racquet in front. Which isn't

very observable from a spectator's viewpoint unless you study the player

instead of watching the ball in play. But for a brilliant player,

that is what it feels like. He doesn't rush because he feels he has all

the time in the world. So enjoy the power as much as you like. Just make

sure you find, or you touch the ball first, then explode into it.

Practical Application

The question that may come to mind is, how does the club player or

the professional for that matter develop this technique? The answer is

relatively simple.

The first thing to do is to follow the ball's trajectory

with your body as usual. No preparation yet, just tracking. Precisely at the bounce, start counting to five. Hold your racquet near

the ball as long as possible and try make contact on the five count,

emphasizing the finish of the stroke.

Gustavo Kuerten practiced the racquet

forward technique when he was a kid and eventually

developed some of the most penetrating groundstrokes in the game.

At first, this may seem improbable, that there can't possibly be

enough time to finish the stroke but I urge you to give it a try. You may

discover that this may be the most "important advice" you'll ever receive

and that "racquet back early" the most

foolish.

Hitting the ball just like that, seemingly waiting, in my mind,

forever, I participated in a more than 400 ball rally with Jimmy Arias,

and he missed first! And Jimmy had one of the hardest forehands in the

world!

This is the type practice I did with Gustavo Kuerten when he was

a kid. I had him stalk the ball until he panicked, then he would hit. The

consequence was that, eventually, he felt as if he had all the time in the

world and developed some of the most penetrating groundstrokes in the

game.

"I urge you to try this technique on all of your groundstrokes. It may

seem difficult at first but you just might be amazed at the results. The

exception to this racquet forward technique is the one handed backhand. In

that case, change your grip and follow the ball with the butt of the

racquet, not the racquet's head."

Oscar

Wegner began his quest to introduce his breakthrough teaching techniques

in the National Tennis School in Barcelona, Spain, in 1973. He encouraged

the coaches and players to follow the topspin style of Spanish great

Manuel Santana, two-time Grand Slam winner Rod Laver, Jack Kramer and Bill

Tilden among other former champions. Oscar's teachings included a natural

open stance on the forehand and swinging across the body, rather than

following the path of the ball.

Oscar

Wegner began his quest to introduce his breakthrough teaching techniques

in the National Tennis School in Barcelona, Spain, in 1973. He encouraged

the coaches and players to follow the topspin style of Spanish great

Manuel Santana, two-time Grand Slam winner Rod Laver, Jack Kramer and Bill

Tilden among other former champions. Oscar's teachings included a natural

open stance on the forehand and swinging across the body, rather than

following the path of the ball.

From 1982 through 1990 he promoted the same

techniques to a large tennis academy for kids in Florianopolis,

Brazil, helping coach Guga Kuerten until he was fourteen.

From 1991 through 1995 he taught weekly on the New

Tennis Magazine Show/ Tennis Television with Brad Holbrook, and, by

Richard Williams own admission "made so much sense that he adopted

them to coach Venus and Serena".

From 1994 through 2000 Wegner worked for ESPN Latin

America and for PSN, commenting on Wimbledon, the French and Australian

Opens, ATP and WTA tournaments, and the Davis Cup.

Oscar is currently in Clearwater, Florida, where he

is developing his website academy, tennisteacher.com