<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

Advanced Tennis

The Myth of the Wrist: The Modern Pro Forehand

by John Yandell

|

Page 2

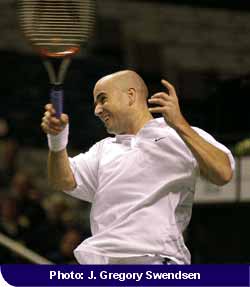

This pro hitting arm position has two elements. First the elbow is bent and tucked in toward the torso. Second, the wrist is laid back.

I call this position—elbow in and wrist laid back—the double bend or “power palm” position. It enables the player to use the palm of his hand to push the racket forward and upward generating power and spin.

The push forward and

upward with the palm of the hand is in turn driven by the rotation of the

player’s torso and hitting arm. This double rotation of the

shoulders and hitting arm, driving the palm of the hand and the racket,

are the keys to understanding the bio-mechanics of the modern pro

forehand.

This first step on the forehand for any modern player is a full shoulder turn, with the left arm crossing the body and the shoulders turned square to the net or even further. This turn is followed by a looping or circular backswing that delivers the racket into position to move forward to the ball.

|

As the racket moves

forward, the torso will now rotate 90 degrees or more back through the

hit, continuing until the shoulders are parallel to the baseline or

beyond. This shoulder rotation drives the hitting arm and the palm

of the hand.

At the same time that the shoulders are rotating, however, there is a second critical rotation. This second rotation is the internal rotation of the hitting arm.

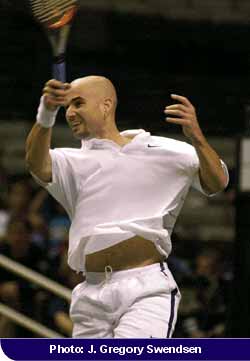

As the racket moves forward, the entire arm is rotating independently, as a unit, from the shoulder. As the high speed digital footage clearly shows, the arm is actually turning over from bottom to top. This rotation can be up to 180 degrees as the racket moves through the swing.

As it rotates from bottom to top, the hitting arm stays in the double bend or power palm position. This means the angle of the wrist and elbow relative to each other remains unchanged. This allows the palm to drive the racket head upward and outward through the shot.

|

The wrist joint itself

plays no role in this forward motion to the ball. There is no wrist

“snap,” “flick,” or “release.” For the double

rotation to be effective, the wrist must remain in the power palm or laid

back position.

Only as the player moves well out into the followthrough and the hitting arm starts to relax, does the wrist begin to release—light years after the hit in the high speed time frame of professional tennis. Since the ball has been off the strings for many milliseconds when this wrist movement begins to occur, it is obvious that the wrist could play no role in generating the hit.

In reality the wrist

release is caused by the forces generating the swing, rather than the

other way around. Wrist movement is a consequence, not a cause of

the motion. It is a natural reaction to the rotation of the hitting

arm. It happens automatically, with no additional or conscious

muscle contraction on the part of the player. In fact, if the arm is

relaxed, it is virtually impossible for a players like Agassi or Haas to

prevent this wrist release from occurring.

Generally, the more extreme the grip, the more extreme the internal hitting arm rotation. The more extreme the arm rotation the earlier and more extreme the wrist release.

|

The amount of arm rotation for a given player can also vary depending upon the height of the ball, and the amount of topspin he imparts. There is also usually more arm rotation on balls that are especially high or low. Generally, the more topspin, the more arm rotation.

On balls slightly above waist level, Agassi will sometimes come through the hit with the racket virtually on edge, a position similar to a classical player such as Sampras. In all these variations, the power palm position and the internal angles at the elbow and wrist remain essentially unchanged.

Why has the myth of the wrist dominated tennis analysis for decades? Because the movement of the wrist after contact is one of the few things that the human eye can actually see in pro bio-mechanics. Possibly this is because the followthrough takes up more time compared to the contact, or possibly it is because the racket slows down during the followthrough.

|

|

For whatever reason, the eye can see that the wrist has moved by the end of the stroke. Unfortunately, this perception has led to the common belief this wrist motion is causally related to the hit.

If you have suffered from a lack of control, consistency, spin and/or power on your own forehand, particularly if you have a semi-western grip, you should examine the role of the wrist and the hitting arm. Develop a feel for the double bend or palm power position, letting your elbow fall in naturally toward your waist. The wrist must move into the laid back position at the completion of the backswing, at the very latest.

|

Now visualize you are driving the ball by pushing the racket forward and upward with your palm. You should try to model Agassi by keeping the palm moving through the line of the shot as long as possible. You can drive the ball with more pace by extending the palm further along this line.

For more

topspin, the hand moves more steeply upward, and the arm rotation is more

extreme. The followthrough should be smooth and long, the natural

unrestricted consequence of a powerful move to the ball, finishing with

the wrist at about eye level.

When working on the hitting arm position, if possible film yourself using a digital camcorder with a fast shutter speed of 1/1000 of a second or more.

Film a

dozen or more examples. Likely you will catch at least one contact point

between the racket and the ball, as well as some good images of your

hitting arm just before and after contact. This will allow you to

compare your actual positions to the animations and digital movies, and

see for yourself how the shoulder rotation, arm rotation and hitting arm

position all work together to drive the ball.

|

By developing and keying on these images, the wrist action on your forehand will find its natural role. You won’t have to think about it. Just relax and let it happen. Focus on the bio-mechanical elements that actually make the stroke happen, and you’ll overcome the myths surrounding the use of the wrist and develop a powerful, reliable forehand no matter what your level of play.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about John Yandell's article by emailing us here at TennisONE.

|

For more information on John Yandell's Advanced Tennis Research Project, click here.

Last Updated 4/15/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.

Visual

Tennis

Visual

Tennis