<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

The Myth of the Pitch

by John Yandell

Page 2 |

|

|

|

A core difference: at contact Pete has uncoiled upward into the air, while Jason has both feet planted in a wide stance. |

|

The Contact Point/Release

Note how Pete makes contact in the air. This is the difference in the role of the legs. The uncoiling is driving his entire body and his arm and racquet upward toward the ball.

Jason is shifting his weight forward and is firmly planted.

Obviously, the contact point for Pete is much higher than the pitching release of the ball. The result is the differing trajectories of the ball described above.

Also note again the angle of the torso.

Due to the tossing position and the “left launch,” (see Sampras

Series). Pete’s torso is leaving the court at a angle to his left.

Jason is almost perfectly straight up and down from the waist.

Finally, there is the position of the head.

Pete has perfect head position, looking up at the moment of

contact, even with his toss fairly far to the left. (See Pete

Toss). Jason,

on the other hand, is looking forward, with his head toward the target zone.

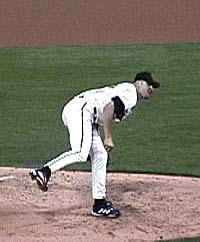

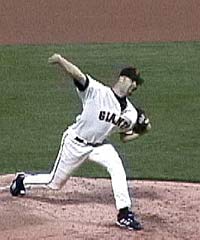

Body Rotation

A key difference is in the rotational sequence in the

two motions. Whereas the

pitcher releases the ball with his torso already facing the batter, the

server is still rotating his torso and is at about a 45 degree

angle to the net at the time of contact.

|

|

A pitcher rotates his torso ahead, parallel to the target zone while his arm lags behind. At the same point in the motion, Pete’s shoulders are still about 60 degrees to the baseline. |

|

If a tennis player with a good feel for throwing a

baseball took the pitch analogy seriously, he would rotate far

too early and end up with his torso much too far around at contact.

In fact, a top Norcal senior player, who was once a Division 1 college pitcher, suffers from this exact problem. His feeling for the release of the pitch leads him to severely over rotate at contact on his serve. The bio-mechanical pattern is so deeply ingrained in his muscle memory that he has never been able to correct it, despite his keen awareness of the problem and of the loss of power it is causing in his serve.

Pros who advocate the throwing analogy can

unwittingly cause this fundamental problem for their students,

particularly those with a strong background in baseball.

The pitcher tends to whip his torso around while the

arm lags behind. This may allow him to generate velocity with a heavy ball

held directly in the hand, but on the serve, this dissipates energy in the

service motion and is widely recognized as a technical flaw, for example

in the motion of a player such as Anna Kournikova.

|

|

Modeling the serve on the pitching motion can lead to a disastrous bend at the waist on the followthrough. |

|

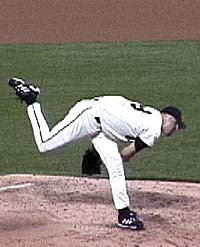

Followthrough

The angle of the torso after the release/hit is also

radically different in the two motions.

A good pitcher, as the animation shows, can end up bent over at the

waist almost 90 degrees as he follows through after the release.

Tennis players in contrast stand up much straighter at the waist

with their shoulders and hips more closely in line.

This probably has to do with the lower trajectory taken by the

baseball.

Again, as any good teaching pro knows, bending too

much at the waist is a disaster on the serve.

It’s a common problem with junior players and even effects top

pros like Venus Williams. The

throwing analogy, taken seriously, can encourage these torso

movements—early rotation and bending at the waist.

Both are destructive to the serve.

|

|

The pitcher releases with both feet on the ground. The server uncoils and leaves the court before contact. |

|

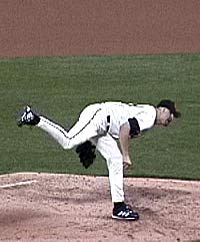

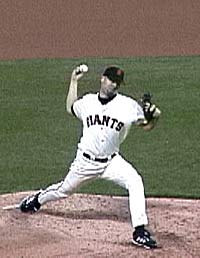

The Legs

The use of the legs is another important, radical difference between the pitch and the serve. The tennis player coils the knees and launches upward and only slightly forward to the ball, making contact with both feet in the air, landing about 2 feet inside the court. The server lands on his front foot and with his feet about the same distance apart as they where at the start of the motion.

The baseball pitcher, by contrast, releases the ball

from a very wide stance with both feet planted firmly on the ground.

During the wind up the pitcher raises his front leg, bends his knee, and brings his thigh back almost to his chest. He then takes a gigantic step forward and plants virtually all his weight on the front foot just prior to the release. The back foot remains back, far behind the front, and is also on the ground. The width of his stance at this point can be 5 feet or more.

|

Anyone who has ever played baseball is familiar with this feeling of stepping, planting, and throwing. Stepping into the serve, on the other hand, is a recipe for bio-mechanical disaster. Stepping with the front foot leads to foot faults and late contact behind the plane of the body. Stepping with the back foot causes over rotation in the torso. Stepping with the back foot can also cause the head and shoulders to drop too soon in the motion.

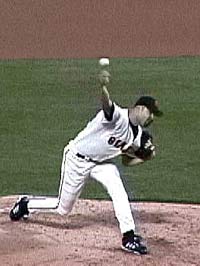

Finally, note the position of the rear leg. When Pete lands in the court, his back or rear leg is in the air. This is the technical end of the motion. He has landed on balance on the front foot, and now has the option to either take the next step forward to the net, or recover into the ready position if he plans to stay back.

Compare this to Jason’s leg. There is a long, almost lazy cross step forward and across his body with his back foot, the natural effect of the continuing momentum of his delivery. Unlike Pete, who takes this step as part of a movement pattern forward, the step for the pitcher is a natural consequence of the delivery. For the tennis player, stepping through the motion in any way that approximates the pitch is a technical kiss of death.

|

|

|

|

In contrast to Sampras above, the pitcher’s weight remains on the front foot and the back leg has taken a long lazy step forward. |

||

Rather than stretching for analogies in other sports,

the key to the serve as well as the other strokes in tennis is a careful

analysis of the stroke itself. This

is the point of many of our series articles, such as the one on Pete’

serve, as well as ProStrokes Gallery.

With ProStrokes you have the chance to see exactly what the top players are doing at each key moment in all the strokes and to use these players as physical and visual models for your own game. Doesn’t that sound like a better idea—modeling your serve on a great server--instead of an athlete from some other sport that isn’t even played with a tennis racquet?

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about John Yandell's article by emailing us here at TennisONE.

Last Updated 9/15/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.