<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

Andre Agassi

The Best Return in the Game

by Jim McLennan

ACTIVE - PASSIVE, HAMMER - NAIL

Tennis is the serve and the return. The server is active, the receiver is passive. The server initiates, the receiver reacts. The server hammers the receiver, or wishes that he could.

So how to handle this reactive situation, the waiting, the receiving, the responding rather than initiating. This may be the single most important stroke in tennis (or equally important as the serve) for it enables the receiver to get into the point and, an error on return of serve is certainly a free point to the server. The receiver cannot swing blindly at the return nor can he simply push the return because of the likelihood of a punishing reply. Simply put, the receiver must return the ball cleanly and with purpose.

|

|

So let us examine Andre Agassi, perhaps the best returner of all time (for me Jimmy Connors is also in this category), to see how to improve your own return of serve.

Ready, Read, React

Agassi crouches, makes a slight ready hop, and as he descends he unweights and begins his turn, almost as though a corkscrew. As the server prepares to strike the ball, the receiver is poised to play, but what is special about this poise at the moment of contact?

At the moment of contact Agassi’s posture is excellent. His knees and ankles are flexed, his back straight. With his head level, his binocular vision is most acute (try looking at something in the distance with your head tilted to one side or the other to verify this) he is now “reading” the ball, to decipher where the serve is going.

Move to the Ball

Agassi begins slightly behind the baseline. From the split step he moves forward yet remains balanced.

No backward movement as he turns his shoulders and prepares the racquet.

|

|

|

|

Waiting |

Ready Hop |

Ready |

Agassi's eyes and head remain perfectly still. He has incredible poise. Note the position of his head on his initial preparation then follow his eyes from the backswing through to contact.

Borrow Pace

The serve is coming so fast the receiver need not overswing to generate additional pace, but rather meet the ball squarely and enable the solid collision to shoot the ball back across the net. Agassi's wrist remains quiet from backswing to followthrough.

|

|

|

|

Turn |

Contact |

Followthrough |

Height of Contact

Note: Agassi meets the forehand above the level of his waist, which importantly is above the level of the net. For recreational players contact height is critical. Meet the ball above the net. Step in and make contact when the ball is at the “top of the bounce” rather than descending well below the waist. The latter case generally occurs when the player does not move to the ball.

Followthrough

Recently, in Tennis Magazine, Agassi’s forehand finish was mistakenly described as having a wrist snap and moving up and over his shoulder. Actually the forearm rolls the racquet up and over the ball, as we see the racquet face at followthrough parallel to the racquet face at impact. Frankie Brennan, Stanford Women’s Tennis Coach, aptly describes this as the “Count Dracula” finish.

|

Recovery

On followthrough Agassi turns initially back to the center of the court, his shoulders are leading his hips, and his first recovery step is not a shuffle but a running stride.

Note how Agassi turns his shoulders into the hit, and then critically, continues to turn his shoulders past the hit and in the direction of the center of the court, virtually turning his shoulders into the running recovery mode. The shoulders lead the hips into the turning movement and that allows the first stride to be a running instead of a shuffling movement.

Of equal importance, Agassi drops the left foot ever so slightly beneath him, call it a negative step, and when done simultaneously with the recovering shoulder turn, this negative step accelerates the move back to center.

If one is not out of position, or being overwhelmed by the power of the opponent, then one can leisurely shuffle step back to center. But in Agassi's condition (or position) a shuffle recovery would be slower and also more effortful, for shuffling takes more effort than running were one to cover a similar distance in a similar amount of time: the running is more efficient. On that, the definition of agility is the ability to move quickly and easily, and for me the negative step of the running recovery is in a word agile. It is Agassi's ability to recover so quickly that makes his returns so much more effective.

|

The majority of the strength trainers working in the tennis arena, Pat Etcheberry, Mark Grabow, Randy Smythe, favor the shuffling movements, but I believe they are unable to distinguish agility from brute force, for they equate court movement with muscular training rather than with technique, with choreography, with ease of movement. McEnroe had this ease about the net, as did Edberg, and now Safin shows this quickness, as did Miroslav Mecir the big cat before him.

Reality Check

To monitor your own reactions when returning serve, (your posture, the precision of your initial racquet preparation), check the following: if the server hits a solid first serve squarely into the net tape (and there is a clear report or sound at this moment), examine exactly what you have done in your return preparations at the moment the ball strikes the tape. Specifically, this serve was half way from the server to you. You had ample time to read where the serve was going, and realistically you had no idea it would hit the top of the net.

But again, at that moment check the following:

- Are your shoulders turned, or are you still facing the net?

- Is your posture erect, or are you leaning either to the side or losing your balance forward?

- Is the racquet slightly back but relatively square, or has it jerked either way up or swung low?

- Have you already stepped in, or is your weight balanced on the back foot?

- Have you flinched or turned smoothly.

This may be one of the best ways to practice, for on each and every squarely hit serve from the opponent that hits the net, you have an instant check on your ability to prepare early and simply, for when that serve hits the tape you should be turned, balanced, racquet square, weight on the back foot, and have done all this quickly easily and with minimum effort.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jim McLennan's article by emailing us here at TennisONE.

|

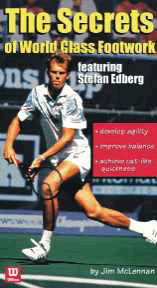

Click here to order. |

The Secrets of World Class Footwork - Featuring Stefan Edberg

Pattern movements to the volleys, groundstrokes, and split step reactions. Rehearse explosive starts, gliding movements, and build your aerobic endurance. If you are serious about improving your tennis,

footwork is the key. |

Last Updated 1/1/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.