|

Lleyton Hewitt: Recovery Artist

by Jim McLennan

|

Hewitt shuffles easily to the ball, note the open stance. |

Lleyton Hewitt has risen to the top of his trade. With US Open and

Wimbledon titles already under his belt, he plays with a ferocity some

liken to a young Jimmy Connors.

Serves pretty good, ground strokes adequate, volleys rarely (he

remarked that he did not serve and volley a single time in his recent

Wimbledon conquest, more or less daring the others to beat him at the game

he chooses to play) but oh can he move his feet.

Rarely out of position, quick as a cat to the ball, retrieving

countless balls that would have been outright winners against less quick

opponents.

When we look at footwork, whether professional or recreational, note

there are three variations. There is movement to the ball, there is

recovery movement

back to the center of the court (actually the midline of the opponents

angle of play) and there are adjusting steps to reposition on the court as

the opponent’s positioning changes.

Players can be cat-like quick to the ball, cat-like quick to recover,

or cat-like quick in all movements about the court. Hewitt is definitely

in this latter category.

|

Hewitt drops the right foot for added quickness to the ball. He

drops the left foot on his open stance recovery move. |

Moving to the Ball

Hewitt’s movement to the ball is extraordinarily quick. Let me

elaborate. When trainers and coaches speak about movement on the court,

they are generally referring to the power or speed of a player, and

indeed, these trainers and coaches ask students to become more powerful in

order to cover the court better.

Yet Hewitt appears quick not powerful, agile rather than muscular.

Agility as defined by Webster is “moving quickly and easily” and for those

interested in improving footwork, the key may be to focus on skills and

drills that increase agility rather than power.

So, to observe Hewitt, first distinguish between balls that require

little footwork, and those where he must quickly move a great distance to

retrieve the ball. In the former instance, he uses either lateral

sidesteps, or a crossover step. Hewitt generally plays the ball with an

open stance, so in these instances sidestepping easily to the ball places

him in an open stance position.

However, on the balls where Hewitt needs to cover a lot of court in a

hurry, he relies a drop step – where he drops the foot nearest the ball as

he turns placing him immediately in a running position.

So how does this effect the club player? I think when an athlete of

Hewitt’s skill uses the drop step for added quickness to difficult shots,

the same technique would help us mere mortals improve our agility about

the court as well. as well.

As a teacher, I have noticed that club players who move easily and

quickly often use the drop step (though in many instances it is

instinctive rather than taught) and those who move slower generally are

sidestepping when they should have been running. Again, the sidestep

inhibits the running gait, the drop step or gravity turn instantly creates

a dynamic running move.

Recovery footwork

Watching Hewitt defeat Jonas Bjorkman in the first round at Wimbledon I

was fascinated by how often he was content to hit the ball perfectly

down the middle of the court, and at other times by the acuteness of his

cross court play.

Then it struck me, he creates angles of play that position him to the

midline of the opponents reply, time and time again. And when positioned

on this midline, it is nearly impossible to get a ball by him.

Generally, recovery footwork is passive, not active. In a center to

center rally, after contact, Hewitt remains more or less near the baseline

divider stripe, and at that spot he is on the mid-line of his opponent’s

angle of play.

In a cross-court rally, after contact, he remains off center, not

recovering fully, as the opponent’s angle of play positions the midline

slightly off center. But in all these instances, the recovery occurs after the shot, and in response to the

location of the shot he has delivered across the net.

these instances, the recovery occurs after the shot, and in response to the

location of the shot he has delivered across the net.

Hewitt, I believe, is active in his recovery style. That is, he plans

his shots in advance so they generally position him exactly on the

subsequent midline. Again, his shot selection minimizes his recovery

footwork; seemingly he chooses shots that require little if any recovery

movement.

Watch him again, when he and his opponent are centered, he often goes

right back down the middle, and in that instance moves not at all after

his shot. In crosscourt exchanges, his angles are generally more acute

than his opponents, this creates a situation where again he needs little if

any recovery footwork steps.

Now when you reexamine his incredible movement about the court, notice

how well positioned he seems to be. And when superbly positioned, it takes

amazing shots to beat him. And with the exception of Agassi at the recent

US Open, rarely are we seeing player’s with the goods.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think

about Jim McLennan's article by emailing

us here at TennisONE.

| Want to read more of Jim McLennan's

unique insight into learning tennis? Check out his other original

articles in the TennisONE Lesson Library. |

|

|

|

|

|

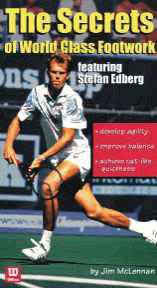

The Secrets of World Class Footwork - Featuring

Stefan Edberg

by Jim McLennan

Learn the secret to the quickest start to the ball, and the secret

to effortless movement about the court. Includes footage of

Stefan Edberg, one of the quickest and most graceful of all the

professionals.

Pattern movements to the volleys, groundstrokes, and

split step reactions. Rehearse explosive starts, gliding movements,

and build your aerobic endurance.

If you are serious about improving your tennis,

footwork is the key.

29.95

plus 2.50 shipping and handling |

|