<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

Percentage Tennis

by Jim McLennan

I read a while ago that Larry Stefanki is now coaching Tim Henman. A small note in the back of Tennis Week acknowledged the Stefanki trademarks to be conditioning and percentage tennis. Stefanki has coached Yevgeny Kafelnikov, before that Marcelo Rios, and prior to that Stefanki was on board to reengineer John McEnroe’s final comeback on the tour.

|

So what is this thing called Percentage Tennis? What playing attributes do McEnroe, Rios and Kafelnikov have in common, if any? Is Michael Chang the ultimate percentage player? Are the original members of the Spanish Armada, Carlos Moya and Alex Corretja so called percentage players? What of the Bellville Basher, 8-time Grand Slam titlist Jimmy Connors? Finally, is the resurgent, yet still unpredictable, Andre Agassi a percentage player? Pause a moment, consider the players mentioned, perhaps pick another player or two from the world rankings who might be considered to play the percentages, and then read on.

Time and Angle

Tennis strategy boils down to time and angle. Serve or return, groundstrokes or approach shots, volleys or overheads - strategy is always about time and angle.

Time: Rob your opponent of time when he/she is out of position (either time to recover or time to run to the ball). Buy time when you are out of position (again either time to recover or time to run to the ball). Rob time by playing the ball sooner, hitting it harder or both. Buy time by slowing down your own shot, lobbing, or throwing in a moon ball.

Angle: Your position on court when hitting the ball determines your angle of play. Measure the angle from your contact point to the sharpest crosscourt and most accurate placement down the line. As you move forward your angle increases, as you back up your angle of play decreases.

Percentage tennis is all about court position and shot selection. Offensive positioning, moving forward, increases your own angle of play and reduces your opponent's time to respond.

This is accomplished by positioning yourself to the midline of your opponent’s angle of play, and selecting shots that reduce your movement back to this midline. So, when cornered during a baseline rally, play the ball crosscourt. Why? Crosscourt groundstrokes position the hitter closest to the midline of the opponent’s angle of play, reducing the potential responses from the opponent. Playing from the baseline, rather than well behind the baseline, increases your angle of play, and reduces the opponent’s time to respond. It will result in fewer recovery steps than if the ball was played down the line. On the other hand, playing an approach shot down the line decreases the number of recovery steps needed, playing a crosscourt approach increases them.

|

Reduce your opponent's angle of play by keeping the ball deep to the corners, or deep and down the middle. From there, the angle of your opponent's response is smaller so you will have less court to cover. Winning tennis - It's as simple as time and angle.

The Short Ball

From the baseline the percentage player generally drives the ball crosscourt, and whenever possible, positions himself on the baseline.

Whenever the opponent hits a short ball, the percentage player moves forward, well inside the baseline. Taking the ball early, the percentage player either approaches the net to finish with a volley, or opens the court with sharply angled crosscourt drives. (Obviously McEnroe or Connors, not Chang, not Phillipousis).The percentage player returns serve from the baseline, rather than taking big swings from well behind the baseline (Phillipousis, Moya), the percentages favor returns met early and from the baseline if not inside the baseline (Connors, Agassi, McEnroe). In the receiving instance, the server has all the offense, the percentage receiver aims for consistent returns, making the server play the next ball.

The percentage player opens the court with spinning serves out wide in the deuce and ad court. Opening the court creates patterns of play for the server, and forces the receiver to choose the appropriate defensive play. In many professional instances today, the big hitters have yet to master the defensive nuances that occur when the serve has moved them out wide. Rios, McEnroe, and Connors, all relied heavily on the wide sidespin serve to the ad court. The Spaniards do not seem to use the out wide serve, preferring to grind rather than to open the court.

The percentage player looks to finish the point at the net. From the net the volleyer has the greatest angle of play, the opponent has the least time. Kafelnikov finishes points at the net, Chang does not. Henman finishes points at the net Phillipousis does not. And certainly who can forget the finishing volleys of Connors and McEnroe.

|

Connors - the master of the all court forcing game |

Rafter - always moving forward, looking to close the net |

McEnroe - perhaps the greatest net player of all time |

Percentage Tennis as a Strategy

Playing crosscourt tennis from the baseline, the percentage player waits for a short reply. Taking this ball early and generally with a down the line approach, the percentage player has run the opponent from one corner to the other, and the subsequent running pass attempt generally leads to a finishing volley to the open court.

Were the percentage player positioned behind the baseline in the crosscourt exchange, they would not be able to move forward as easily or take the short reply as early. And in this unfortunate instance, the opponent is not “punished” for their short shot. So the percentage player is always looking to move forward, always looking to increase the bet on short balls, always looking to apply pressure on the opponent.

|

|

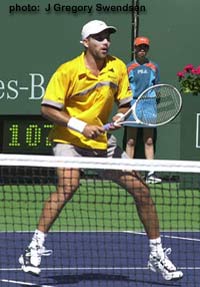

Applying constant pressure from all areas of the court, Stefan Edberg (right) dismantled Jim Courier's power game in the final round of the 1991 US Open. |

|

I called a number of tennis friends asking their opinions about percentage tennis and percentage players. Bill Strei, an old friend doubles partner and mentor, surprised me when he answered Jack Kramer. Kramer, as he reminded me, always moved forward looking to finish the point at the net. How simple.

1991 - Stefan Edberg VS Jim Courier

As an example of percentage tennis, in 1991 Stefan Edberg dismantled Jim Courier in the final round of the US Open. Applying constant pressure from all areas of the court, Edberg attacked any and all short balls, volleyed with deadly authority, and served consistently throughout. Particularly telling were the baseline rallies with Courier, where Edberg used far less pace, yet moved forward immediately on any ball Courier hit with less than maximum depth.

Watching Couriers game unravel, it was easy to assess the

effect of Edberg's style on his opponent's skills.

The following reprint summarizes the "All Court Forcing

Game." Tom Stow taught that the constant pressure applied against a

human opponent would produce just the results we saw at the Open.

As we move into an era where sport science applications abound, it

is nice to read of an "innovation" from the 1940's that has

particular relevance to the game today.

"The Forcing Game" from The Tom Stow Tennis Teaching System, (1948)

The forcing game is based on the principle of

continuous pressure. It is a

game for advanced players who have acquired all the strokes and therefore

are able to control the ball from all positions.

It should be called an "All Court Forcing Game" for it

is too often confused with just a net game.

Coming into the net is definitely a part of the game and should be

used as a climax to many rallies or when the opponent hits a short shot,

but is only a part of the whole. A

player who can make sound "coming in" shots and can volley

accurately will be a constant worry, for his opponent in trying not to hit

short balls will tend to make more errors than he would otherwise.

|

To play the "All Court Forcing Game" it is necessary to have;

-

A strong first serve and an accurate spin for the second serve. A hard first serve, which will put the opponent on the defensive and cause errors, is of course the best. However, this is not absolutely essential but a serve that will keep the opponent from making a forcing shot is essential;

-

The ground strokes, both forehand and backhand must be sound so that;

-

The return of the serve be deep

-

The shots from the back court be firm and well placed

-

The coming in shot be hit flat on the top of the bounce.

-

-

The volley must be accurate and fast enough to put the ball away. A blocked volley is not enough; a player with only this type of shot cannot win the point when the opening appears.

-

The smash is a must in this type of play for the opponent of a player with a weak overhead can lob defensively too often. This does not give the forcing player enough percentage off of his approach shots and he will find himself in trouble. Smashes, like volleys, must be put away, not only from the standpoint of winning the point but also the mental effect such shots will have on the opponent.

The player of this "All Court Forcing Game"

must always keep in mind the fact the he is playing another human being

and that the pressure he is applying has a very definite effect on the

mental attitude of his opponent.

It takes nerve, determination, and strokes to play this type of game and only the strong will master it. However, from these few will emerge the future great players of the world. (Read, McEnroe, Connors, Agassi, Kafelnikov, perhaps Rios can do this, and now we wait and see about Henman).

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jim McLennan's article by emailing us here at TennisONE.

|

Click here to order. |

The Secrets of World Class Footwork - Featuring Stefan Edberg

Pattern movements to the volleys, groundstrokes, and split step reactions. Rehearse explosive starts, gliding movements, and build your aerobic endurance. If you are serious about improving your tennis,

footwork is the key. |

Last Updated 12/15/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.