<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

The Bat Cave:

How James Broder Created An Electronic Brain for the U.S. Open

by John Martin

Copyright 2000

Photos Courtesy of ABC News

It is Super Saturday of the 2000 U.S. Open. Marat Safin and Todd Martin are stroking forehands, warming up for their semifinal match. Deep inside the stands, beneath the seats of Arthur Ashe Stadium, a young couple walks down a bare hallway. Without a glance, they pass a doorway marked by a small blue sign in white letters: 1341 Stadium IBM

|

Inside, spread on tables along two walls of a vast square room, more than a

dozen television monitors and computer screens flicker with images of tennis

players, stadium and grandstand courts, and streams of data.

Nearly a dozen men and women, wearing white tennis shirts, khaki or denim

shorts, and red-bordered plastic ID tags, look up at the screens.

Occasionally, they move back and forth between tables, leaning to click

strokes on keyboards.

This is the Bat Cave, the nerve center of a giant electronic brain created

to observe every U.S. Open tennis match played in the two weeks of

competition.

"We can track every point of every match," says James Broder, the software

ringmaster of what amounts to a three-ring circus of tennis geekdom. "The

umpires," he says, "they're providing content."

|

It's a prodigious feat, so specialized and sophisticated that it has propelled Broder, its software creator, into an entrepreneurship that now spans an international sports world far beyond Grand Slam tennis, which also includes the Australian Open and the ATP Tour Masters Series.

Broder's scoring and timing universe now covers the Winter Goodwill Games

(ski racing, bobsled, luge), the bicycling Tour de France, the World

Equestrian Championships, World Cup velo (track cycling), World Junior Velo

Championships, Tag Heuer World Cup ski racing, and the

NASCAR race car circuit.

Broder's Skunkware, as he calls it ("Radical Software that Shreds"),

supplies not only minute-by-minute scoring and timing for spectators on the

grounds of these events but also for millions of television viewers around

the globe.

That James Broder should contribute to this triumph of computer technology over the statistical blizzard generated by international sport is especially astonishing, considering that in the early 1980s, the same James Broder was a failing economics student facing dismissal from the Vanderbilt University School of Business.

"It was the statistics," he says, noting that as a Yale undergraduate he had not used computers. "I had to get a handle on statistics and I realized that computers were the way for me to tackle them."

It was an epiphany.

Within a few months, Broder, who had ranked 33d in the nation among 16-year-olds tennis players in 1976, wangled a $1,500-a-month summer internship with the women's pro tour ("I was a grunt"). His new skills came in handy.

|

"They needed a new computer ranking system," he says. "It was a big problem.

They had a black box and a process so complicated nobody understood it."

The year was 1983 and the unfathomable women's tour rankings were sowing

distrust among the players.

"It was still the Cold War," says Broder, "and this was an American tour.

The Czech and Polish players and coaches were suspicious."

One weird element of the WTA rankings raised the hackles of everyone, not

just the East Europeans: Tracy Austin was still ranked among the top five

players in the world 11 months after leaving the tour with injuries.

"The answer," notes Broder, "was a 52-week weighted, moving average." That

meant finding a way to rank players not only on recent matches but also

continue counting older results.

It was a juggling performance only a geek could love. But Broder swooned and

produced a system still in use today, creating software to take the measure

of the players' wins and losses at regular intervals.

One of its earliest successes: Charting the ups and downs created by the

rivalry of Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova.

After an experimental tryout, the system was approved by a vote of the WTA

in 1984. Broder was on his way.

"I got calls from television production companies," he says. "They were

involved with sports which were not furnishing enough data."

So television's voracious appetite for statistics had to be satisfied. That

meant learning the intricacies of sports he had never witnessed.

|

Pro Beach Volleyball, with its Baywatch aspects, may have been easier to

watch and surely easier to comprehend than NASCAR scoring and timing.

Nevertheless, Broder plunged in.

"We developed a collection software to put the data on the air," he says. It

was a breakthrough for promoters, TV producers, and, not least, a software

creator named Broder.

Now, moving from event to event, Broder assembles teams of programmers, some

employed by his partners in sports technology: Phoenix Sports Technology of

Trexlertown, PA, which uses his V2 timing software for track cycling; MatSport of Grenoble, France, his Tour de France

partner; Precision Timing of Montreal and Utah, which runs the Tag Heuer World Cup Ski

Racing software operation; and Information & Display Systems of Jacksonville, which holds

the U.S. Open contract.

"I really don't much like being general contractor," says Broder. "I prefer

to design and write software tools."

The contracting teams handle organizational details, dividing duties, such

as monitoring "packets," the data traffic flowing into their control rooms,

looking for failures throughout the system.

|

At Flushing Meadow, disaster can strike at any time. Cables can be damaged,

power losses can cripple signals, giant screens can flip images, the "rocket

launchers" used to load match information into the chair umpire's computers

can malfunction.

Vandals can also play a worrisome role. Besides excessive heat, component

breakdown, and tears in video walls, his 50 scoreboard technicians must

contend with theft.

"Somebody walked off with a flat-screen monitor worth $1,500," says Broder

as we sit at his desk in the cave. At last year's U.S. Open, no fewer than

16 laptops were stolen from outside trailers.

"This tournament is a train wreck waiting to happen," Broder says, comparing

his team's work to "collecting garbage in New York City." Every bit of data

is being picked up.

In Broder's world, no matter who is winning on the stadium court a few

hundred feet away, the Bat Cave is serving "clients" with a continuous

stream of data.

Its biggest customers are 150 broadcast producers and tournament officials

armed with laptops. And the most vital components are the scoring devices

operated by 42 chair umpires across the National Tennis Center.

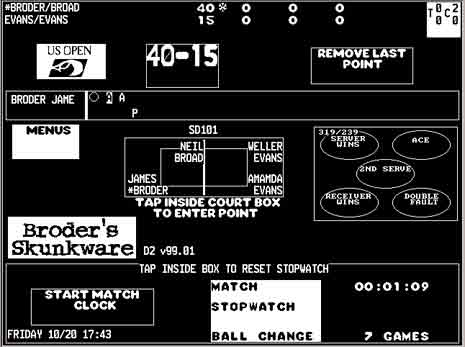

Anchored in their docking stations atop the chairs, these hardback

book-sized computers are linked to the Bat Cave's 10 servers.

On the scorekeepers' screens, like some multiple-choice exam, are the outlines of half-a-dozen pressure points: Ace, Double-Fault, Forced-Error, etc.

|

|

|

When an umpire taps the screen to record a point, the signal changes the scoreboard on court, and then travels to the Bat Cave, where it is flashed across boards all across the complex.

"The (score) boards on each of the match courts are (composed of)

electro-magnetic flip disks," says Broder. The big scoreboards, like the

giant screens atop the Ashe and Armstrong stadiums, use banks of lamps in

red, white, and yellow to flash their messages, including the colorful "Rain

Delay."

Next year, Broder is switching the scorekeeping system to hand-held

devices. "Rather than using the relatively unwieldy IBM 4612 'wristwatch'

computers," Broder says, chair umpires will be issued PalmPilots "to drive

the entire Bat Cave system."

Broder is optimistic: "It should be a neat application of Palmtop

technology." Not surprisingly, IBM will play a role. The hardware will be

IBM Workpads, using a PalmVX model.

If it works, it will be a wondrous thing. If it fails, of course, it could be a monumental disaster. That's because Broder's Skunkware presides over an orgy of information gathering --- and transmitting. The servers contain drives that not only keep score but provide closed-circuit video for the complex.

Beyond that, IDs sends out a team of 24 professional statisticians to take down the raw data courtside on virtually every important match: net approaches, forehands, backhands, overheads, first-serve percentages.

Both the statisticians and the umpires feed the cave dwellers a stream of match statistics that are sifted, then reprocessed to create match data that can be used by the USTA to serve the off-air press as well as broadcasters.

|

|

Below the Ashe Stadium stands, USTA runners deposit sheets of these statistics in rows of boxes at one side of a vast Media Room. From here, reporters work in more than 250 cubicles equipped with electricity, telephone lines, television monitor, and reams of fact booklets. Thanks to Broder's team, the journalists continually dip into the boxes for statistical comparisons it would take them hours, if not days, to amass on their own.

Why call it Skunkware?

"I originally named it Broder's Skunkworks," he says, "in tribute to the

(secret) division of Lockheed, which built the SR71 spy plane." But Lockheed objected, warning Broder not to use

the term and even going to the trouble of suing a dictionary which defined the word without

mentioning the giant aerospace company.

"After some legal exchanges, my attorney told me that Lockheed's brand mark

clearly extended only to aerospace products," he says, "and that should the

matter go to court, I would win in a slam dunk."

|

|

Even so, with a potential legal bill of a quarter-million dollars to secure his rights, Broder backed off. "I simply changed the name to 'Broder's Skunkware'. I now own that brand mark, so Lockheed can kiss my ass."

Broder insists "I am not a dot-com zillionaire, but I do pretty well. I make about as much money as a reasonably successful doctor in private practice.

"Money isn't really the object of my game," he says. "I could no doubt make twice as much if I worked in software development for Sun or some other Silly Valley juggernaut."

What gives Broder a feeling of satisfaction is his ability to out produce big corporations, using his philosophy of small-is-better and what he calls the "power of small and clever."

As proof, he points to his nephew, Christo Wilson, his 16-year-old protégé who programs the software used on the handheld computers at the Open. "He can program circles around the average MIT computer science graduate."

From above, the crowd's roar sinks into the recesses of the Ashe Stadium structure, rolling down the corridors and blotting out the keystrokes and conversations that might escape from the Bat Cave.

"Years ago," says Broder, explaining the term, "we ran the U.S. Open

computer operations out of a tiny room under what used to be the Grandstand

Court (of Louis Armstrong Stadium). "It was hellish. The power blew out at least once a day, the air

conditioning never worked, the room flooded. It was a nightmare."

Faced with those working conditions, Broder says he named it the Bat Cave "because the room

was so tiny and airless, yet it was crammed, literally, to the ceiling with electronic gear."

Now, with yards of space, the scene is different:

As we wait for the Safin-Martin match to end, the Broder team kicks back.

Someone pulls out a football. With hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth

of equipment lining the playing field, they toss laterals and passes back

and forth. Quarterback Broder takes his turn.

The cave dwellers are at rest -- and play.

John

Martin, an ABC News National Correspondent, is the founder and editor of

Aztec Tennis Reporter, a worldwide newsletter for the San Diego

State tennis community.

John

Martin, an ABC News National Correspondent, is the founder and editor of

Aztec Tennis Reporter, a worldwide newsletter for the San Diego

State tennis community.

To receive the Aztec Tennis Reporter, write to John Martin, 1528 Corcoran St., NW, Washington, D.C. 20009.

Copyright 2000, John Martin

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you about think

John Martin's article by emailing

us here at TennisONE.

Last Updated 11/15/00. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.