The Struggle for Women's Collegiate Tennis

by John Martin

Copyright 2001

Photos by John Martin (Courtesy ABC News)

In 1874, a woman named Mary Ewing Outerbridge of Staten Island, NY, introduced lawn tennis to

America.

In 1945, by the reckoning of the United States Lawn Tennis Association, young Jeanne Doyle of California

ranked second in America in junior girls' singles (behind Shirley Fry).

Jeanne Doyle was good enough to beat a lot of guys on the 1945 San Diego State

tennis team but was not allowed to compete.

|

But when Doyle entered San Diego State College that fall as a freshman, she

looked in vain for a women's team and practice partners. There were none. So, like a small number of competitive young women of her

day, she hit with the men's team.

"She was good enough to beat a lot of guys on the ladder," says Walt Palmer,

who played on the 1946 Aztec squad. "She would have had a shot at it," says

John Brock, who played number one on the 1948 team.

Doyle herself has no doubt: "I was good enough to make the team."

But Doyle did not make it. Despite the gains women had made during World War

II, there was a glass wall keeping all but a handful of women off the men's

courts and out of team competition.

Today, some 6,000 young women compete for tennis scholarships and ladder

positions on more than 800 American college teams. Tennis is counted as a major women's college sport, deserving of full funding and

strong promotion.

In a remarkable role reversal, men now struggle on some campuses to find a

men's team: In 1998, a survey of NCAA Division 1 schools for the USTA found

that in the previous 20 years, 36 universities had dropped men's tennis as a

sport.

By all odds, women's collegiate tennis has nothing to answer for such problems. For decades, it suffered

back-seat funding and front office discrimination.

"The coach checked and said they would not allow it," says Doyle of her 1946

encounter. "Even the women (school officials) did not want me to compete."

Then one day, she met Jesse Owens, the 1938 Olympic champion runner, who was

visiting campus to make a speech.

Introduced by a coach, Doyle and Owens began talking, heart-to-heart, about

the barriers they faced in mid-century America: A black sprinter and a female tennis player.

When Owens got up to speak, Doyle was astonished: "He told of having met me," she said, "and how, being

black, he had his problems of being accepted. And here was somebody at San Diego State who was more

or less an elite athlete who could not participate."

Golden balls are awarded to the champion of a USTA National Event.

The fabled

Dodo Cheney, now in her eighties, has won 300.

|

Doyle was energized. In 1948, after a year out of school following her father's death, she transferred to the

University of Arizona, which fielded a women's team whose members were allowed to compete in

tournaments, but only as individuals.

Doyle not only won intercollegiate titles representing the Wildcats in California, Arizona, Oregon, and

Washington, she later coached men's and women's college teams, and succeeded in racking up an

astonishing 50 gold balls in USTA competition at various age levels (By contrast, the fabled

Dodo Cheney has won 300 gold balls).

Today, some fans blame the Title IX revolution for damaging men's intercollegiate tennis. Under a Federal

law signed in 1972 by President Nixon, colleges which receive Federal funds must ensure gender equity.

But is women's tennis to blame for cutbacks in men's tennis? The USTA survey

found a combination of factors, including both financial constraints and gender issues. Writer and columnist Frank Deford identifies

another villain: football.

"Football (men only) is a pig," he says, pointing out that it gobbles up the

largest share of virtually every university's athletic budget.

Still, by almost any measure today, this is the age of women in tennis. Not

only is Venus Williams captivating the Royals (and the world) at Wimbledon,

but the veterans are reaping rewards and recognition: Martina Navratilova

is performing in an automobile commercial, and Billie Jean King is starring

(as Holly Hunter) in a made-for-television movie ("When Billy Beat Bobby")

chronicling her breakthrough for women a quarter century ago.

So what do women want?

A fair chance. A square deal. The opportunity to compete on a team.

Does teamwork matter? A 1999 National Science Foundation study of 26,200 high school girls found that

those who played on athletic teams or were exposed to sports (not as cheerleaders) were far more likely to

tackle science subjects which prepared them for professional careers in such fields

as engineering and medicine.

"The ability to compete, independence, self-esteem - the tremendous benefits

reaped from sports participation - are the same traits women need to succeed

in science," concluded the study's authors.

Since the advent of Title IX, the number of female high school athletes has

jumped from 300,000 to more than 2,000,000. Today, one out of every three girls in high school competes in sports (one of every two

boys competes).

Still, no matter how far they've come (as that tobacco company used to remind them and us) it's important

(and humbling) to turn back and see how little team competition women were allowed to experience in

tennis.

College tennis is a good place to look. The men's championship opened at

Trinity College in Connecticut in 1883 and is the oldest collegiate title in

America. The first national women's collegiate championship was not held until 1958 at Washington University in St. Louis. The sponsor was the USLTA.

True, between 1883 and 1982 (when the NCAA finally stepped in to stage a women's tennis championship)

females competed on all levels within the USLTA. But for nearly all of those 99 years, women on college

and university campuses struggled with a sense of being outsiders in a world of athletics

dominated by males. The social - and legal -- barriers were high.

Women were the exceptions on intercollegiate tennis teams dominated by men.

It was not that male-dominated athletic departments -- still in their ascendancy -- saw little need to offer athletic

scholarships to women. It was the law: NCAA rules barred women from receiving financial assistance as

athletes.

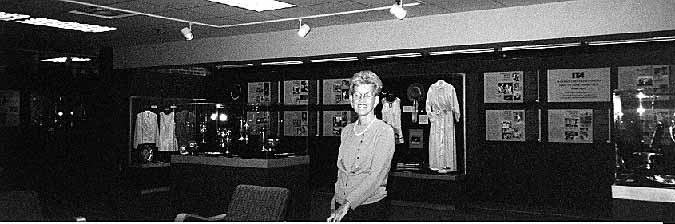

Millie West in the Women's Intercollegiate Hall of Fame trophy room at the

College of William and Mary in Virginia.

|

The only recourse was the courts. In 1966, frustrated by her inability to

coax top players with scholarships to her teams at Florida's Marymount College, a 22-year-old coach, Fern "Peachy" Kellmeyer, sued the NCAA

to overturn the no-scholarship rules. She won.

(Kellmeyer was a pioneer as a player, as well: At the University of Miami,

where she was number one on the women's teams in 1964-66, she became the first woman to play on the men's team. Today, she is enshrined

in the Intercollegiate Women's Tennis Hall of Fame at William & Mary College in

Virginia).

Millie West: Without Title IX male athletic directors would have ignored women's tennis with impunity.

|

But even after Kellmeyer's legal victory, the changes were glacially slow.

Women who wanted to compete were still forced to play mainly outside the university athletic universe.

In 1968, 32 years after Jeanne Doyle's turn down at San Diego State, the university still saw no reason to

support a women's tennis team. So Valerie Ziegenfuss, a student with vast tennis talent, attended classes and

took time off to play USTA tournaments, earning a top ten ranking. She was one of

the WTA's founders, a pioneer compatriot of Billy Jean King.

Doyle's status is interesting. She is a candidate for the Women's Intercollegiate Hall of Fame at the College of William and Mary in Virginia.

"Oh, yes," said Hall Director (and former Athletic Director) Millie West, "I

have a file on her." Doyle is one of a number of players under consideration

for a spot in the hall, which is housed in the McCormack-Nagelsen Tennis center. Among the 1997 inductees was Darlene Hard of Pasadena, CA, who

won the 1958 inaugural national women's intercollegiate championship.

West, who presides over a modern trophy room filled with cups and plates and

memorabilia, says Title IX was an absolute necessity. Without it, she says,

male athletic directors would have ignored women's tennis with impunity. With legal sanctions looming, they must act.

West is worried, however, about the loss of men's tennis teams on college

campuses. She led the 1998 USTA study and urged reforms, including guarantees for male players whose schools attempt to terminate

their programs while they are on scholarship.

"If gender equity interpretations continue (based on male/female enrollment

proportions)," she wrote, "it is clear that new sources of funding...must be

developed if we are to curb the elimination of (men's) intercollegiate tennis programs."

San Diego State finally fielded a women's team in

the mid-1970s. Under Coach Carol Plunkett, the Aztecs ultimately

reached fourth in the nation.

|

On the other side of the issue, Dan Magill, the former University of Georgia

coach who brought the NCAA Intercollegiate Men's Tennis Hall of Fame to Athens, GA, says Title IX was unnecessary.

"Women didn't need it," he said. "They already competed against each other

in tennis."

But it was not until 1963 that Magill's own SEC Conference allowed women to

play intercollegiate tennis for the first time, and then only if they could

fight their way onto a men's team.

One who did win acceptance in 1963 was Becky Birchmore, the Georgia state women's champion. As a

senior, she played second substitute on the University of Georgia men's team - and seems to have vied

successfully with men over the years in a number of endeavors: Today, she is a patent lawyer

with degrees in medical microbiology, the law, and medicine.

Finally, in 1972, with the passage of Title IX, the door began to swing open

for more women.

San Diego State finally fielded a women's team in the mid-1970s. Under a

Women's Coach Carol Plunkett (now retired and living in Portland, OR), the

Aztecs produced 14 All Americans and rose as high as fourth in the nation.

Jeanne Doyle is pleased - more than half a century later.

Despite the obstacles endured by women of her generation, she persevered and

prevailed. Why did she persist? "I just love tennis," she says, "win or lose."

John

Martin, an ABC News National Correspondent, is the founder and editor of

Aztec Tennis Reporter, a worldwide newsletter for the San Diego

State tennis community. John

Martin, an ABC News National Correspondent, is the founder and editor of

Aztec Tennis Reporter, a worldwide newsletter for the San Diego

State tennis community.

To receive the Aztec Tennis Reporter, write to John Martin, 1528

Corcoran St., NW, Washington, D.C. 20009.

Copyright 2001, John Martin

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you about think

John Martin's article by emailing

us here at TennisONE.

|