|

SpotLight: Ilie Nastase

By Sean Egan

Today, Ilie Nastase is merely a face that pops up when TV leavens its

coverage with comedic clips from bygone days: an image from the age of

wooden racquets humorously holding an umbrella on court or taking issue

with Cyclops. Few who didn’t see him in action in his heyday or who are

not aficionados of tennis history would realize from such footage that

Nastase was one of the most breathtakingly gifted players of all time. To

some, he was literally the greatest. Yet even those who sing his praises

say he underachieved, letting his hot temper and his propensity for

buffoonery cheat him of too many titles that were his for the taking. An

indication of just how great a player he was is the fact that even in a

career of what is universally acknowledged as unfulfilled promise, he

claimed championships at the French Open and the US Open as well as an

unbelievable four Masters victories.

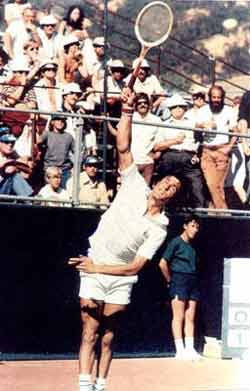

Here Ilie is seen clowning it up but Nastase was also one of most

breathtakingly gifted players of all time.

|

Ilie Nastase was born in Bucharest, Romania in 1946, the youngest of

five children. His father started out as a police officer but in time

moved over to banking work. In a country then in the grip of communism,

young Ilie found refuge from his grim surroundings in sport. He was gifted

in several but especially soccer and tennis.

“I have the feeling that every sport I played with a ball, I [had] a

very good touch either way,” he says in the endearingly fractured form of

English he made familiar at press conferences in the Seventies. “I played

basketball, anything. If the sport has a ball, I’m very talented with

that.”

Opportunities for practice at tennis were plenty: Nastase’s family

lived in a house that was situated in the bounds of a tennis club.

Nastase acknowledges that this was a very important factor in his life. “I

think it was the basing of becoming a tennis player because I was a ball

boy and I was very close to the good players when they play in the club or

Davis Cup and I follow all the players everywhere,” he reveals. “I learned

quick and that’s what’s for me the preparation to become a good player.”

Though Nastase, of course, had some coaching and practiced hard in his

early days, he was one of the few players in history (John McEnroe was

another) whose skills were essentially in-born: his instinct, anticipation

and quicksilver shot selection were the type of things that simply could

not be coached. “It was natural,” he says. “I didn’t have to worry too

much what’s coming. I had a lot of intuition for the game. I know ahead

what the ball was coming and things like that. I was lucky to have this

talent or whatever you call it: gift from God. It’s helpful if you don’t

have to practice so hard. For me, everything was natural.” This natural

ability meant that Nastase could afford to spurn conventional techniques:

“It’s different when you play the way you want and then you see players

playing different. For me, it was like, ‘I have to do it my way’. I did it

for myself. I pleased myself and if I pleased somebody else, people around

the world, even better - but I did it for myself.”

This Gift from God made Nastase a stark contrast to many of his rivals

when he became a professional. Asked whether he felt sorry for someone

like Bjorn Borg, who was rarely off the practice courts, Nastase says,

“No, because it’s a talent that way too. If you ask me to practice five

hours, I can’t do that but there are not many players like [me]. The only

player I see in the world today I guess like me is Martina Hingis. She

knows where to go before the other girls hit the ball. She’s very good

intuition. You cannot practice at this.”

Nastase was a new breed of player, he argued with umpires, tormented

his opponents, and engaged in silly antics

|

Despite his natural skill, Nastase didn’t actually start playing on the

circuit until he was 21, a very late age even then. He feels this may have

handicapped him in a couple of ways. Firstly, it meant he didn’t have as

much time to acclimatize to grass as his rivals: “The problem was because

I build my tennis on clay,” he laments. “Being brought up on clay, because

the courts were so slow. I never had a chance much to play on fast

courts.” It wasn’t until he was 21 that Nastase even saw a grass

court. The second handicap was the way his backhand - always the weakest

shot in his armory - failed to mature: “I developed maybe a wrong shot,

that was my backhand. It was difficult for me to go in the big tournaments

and improve it quick.” However, another possible explanation for his

underachievement was something that couldn’t really be blamed on his late

start: his emotionality. “Everything bothered me,” he admits. “If someone

was moving in the stadium or the staircase. Some guys like Bjorn never

let anything bother them at all.”

When Nastase did start playing on the international circuit, it became

clear before very long that here was a new breed. A sport that still

dripped with country club connotations - and which for the first few years

of his career was still contaminated by the hypocrisy of ‘shamateurism’ -

simply wasn’t prepared for Nastase’s kind of character. He argued with

umpires in the most profane language imaginable, tormented his opponents

with blatant time-wasting and psychological warfare and engaged in silly

antics designed to alternately please and alienate the spectators. He was

thrown out of tournaments, suspended and fined again and again. All of

this produced a rather inevitable nickname: “Nasty”. (“The Bucharest

Buffoon” was another favorite insult of his detractors.)

Yet for many, his sublime talent made everything forgivable. He was

tennis poetry in motion, gliding around the court with incredible speed

and an apparent effortlessness. Equally fast and fluid was his

shot-making, switching grips in the blink of an eye to produce exactly the

kind of stroke his opponent assumed he couldn’t possibly manage. Charlie

Pasarell once marveled, “Sometimes you find him just standing there

waiting for the shot.” Topping off those in-born skills was a quality

Nastase achieved by the practice normally alien to him: a thunderous first

service.

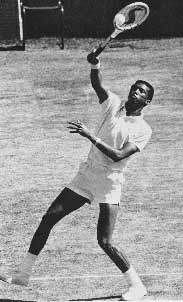

Despite storming out of their match at the Masters, Arthur Ashe

remained Nastase's friend.

|

Not that it was mere talent that provided Nastase with absolution. That

he was a man as warm-hearted and friendly off-court as he was spiteful on

court ensured that even the players he tormented found him lovable. The

dignified and aloof Arthur Ashe, for instance, was an unlikely friend and

remained so even when he stormed out of their match in the 1975 Masters

tournament in exasperation at Nastase’s antics.

The mixture of Nastase’s graceful talent and graceless behaviour soon

made him the biggest box office attraction the game had hitherto seen and

helped attract a younger audience that had previously disdained the sport.

Nastase is unrepentant about his behaviour, despite the widespread

feeling that it prevented him fulfilling his potential. (One commentator

once described him as “The best player with the worst results of all

time”.) “I don’t know,” he shrugs when that issue is put to him. “That’s

somebody else’s problem. I only want to be myself and if I look back

then, I don’t have any regrets. That’s the way I feel to play the game.

Maybe. I don’t know. Maybe if I wasn’t the way I was, then I didn’t win

anything. It’s to prove.”

Nastase was also accused of looking down on players whose games weren’t

as stylish as his own, even to the point of mocking them by reproducing

their own boringly orthodox shots for stretches of matches. Nowadays, a

mellower Nastase is almost offended by the suggestion of disdaining the

less gifted: “No, no, no,” he insists. “I didn’t do this. Just, maybe

the way I was playing, the way I was taking the other man, but no, I never

put anybody down or said they are not good players.”

Nastase won his first non-Romanian title in 1967. The first of his two

Grand Slam titles came in 1972 when he beat Arthur Ashe in the final of

the US Open, astounding even himself by winning a tournament played (then)

on grass. The following year, he defeated Nikki Pilic to claim the French

Open. (He’d finished runner-up to Jan Kodes in 1971). He should also

have won Wimbledon but was always the bridesmaid at the All-England Club. In 1972 he was defeated by American Stan Smith in a stunning final which

many still talk about as the greatest ever played there. In 1976, a last

hurrah at the age of 30 was only stymied when new young hope Borg beat Nastase to take the trophy.

Nastase’s best tennis, however, was reserved for the Masters. “The

last tournament of the year - maybe everybody was tired!” Nastase now

suggests in an uncharacteristically modest way. The season-ending

tournament which sees the top eight players in the world congregate to

determine who is the crème de la crème was an occasion to which Nastase

always seemed to rise. He often became bored when taking on lower ranked

players (“That was my problem” he admits) but put a superstar in front of

him and Nastase suddenly became alert and eager to prove a point. For

three years on the trot - 1971 to 1973 - he won the title. In 1974, he

was defeated by Guillermo Vilas in the final but came back triumphantly

the following year to reclaim the title by trouncing Bjorn Borg losing only five games. Not even Pete Sampras - so

dominant in his own era - has been able to best his closest-placed peers

so consistently.

When the computer rankings system was first introduced in 1973, Ilie

Nastase was its first number one.

|

Of Nastase’s more than one hundred titles, about half were doubles,

inevitable for a player with such lightning fast reactions. In mixed, he

partnered Rosemary Casals while he had a variety of partners in men’s

doubles, the most notable of which was Jimmy Connors, a player with a

temperament very similar to his own. “We played for three or four years,”

Nastase remembers of his partnership with the pugnacious American. “The

time we finished, we’d been defaulted many times. But finally we won two

grand slams. Playing with Jimmy was fun. A lot of fun.”

Nastase was the first ever number one in the computer rankings when

that system was introduced in 1973, something he is very proud of: “I want

to be remembered like a number one. I’m one of the few number ones in the

world. For me, it’s a great pleasure to be with all these guys. I think

there are twelve or thirteen only, until now.” He feels that the computer

rankings were a change that had to be made. “I think the rankings before

[’73] was a problem because it was not computer and the sport writers,

they make the rankings,” he points out. “Then when the computer came in I

thought it was a good system.”

However, he does acknowledge that there is perhaps something unhealthy

in the lack of competition to the ATP. In his day, circuits such as World

Championship Tennis were alternatives considered equally valid to the main

tour. “I think it was okay then,” he recalls. “Many players, they can

choose a tour. Now, I don’t know if there is a monopoly, but players,

they cannot choose. They have to play ATP. Every single tournament is an

ATP tournament. But I think ATP are doing quite a good job. What they’re

doing now, they’re trying to cancel some tournaments because obviously

there’s a lot of tournaments and, players, they cannot play everywhere and

every week.”

Talk of the modern game brings up the subject of players Nastase

considers in his own elegant image - or rather, the lack thereof, Hingis

excepted. “He’s not playing anymore but a guy from Czechoslovakia -

Miloslav Mecir,” Nastase says. “But I don’t know anybody now doing that.”

When asked whether he agrees with the perception of many that players

today treat the game too much like a business to the detriment of fun, the

once outspoken Nastase is surprisingly coy: “I don’t know. I think the

game is different, the players are different, and I don’t want to compare

with when we played and what we do.” When it’s suggested to him that the

game is generally considered less exciting now, he only offers: “I don’t

know. I think it’s different and I cannot comment more than that.”

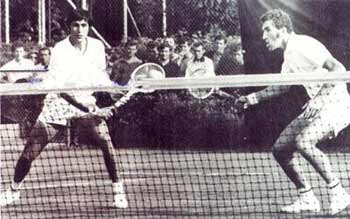

A gifted doubles player, Nastase won more than fifty titles, many with

long time partner Ion Tiriac.

|

Such coyness is a measure of the fact that Nastase - while in no way an

establishment figure - has come a long way from the man of scandal of the

1970s. For example, in 1996, he stood as a left-wing candidate for the

post of Mayor of Bucharest following his country’s conversion to

democracy. Although he didn’t win, he surprised many with his thoughtful

campaign. Meanwhile, he was until recently a part-owner - with former

doubles partner Ion Tiriac - of the Romanian Open ATP Tour event. “It was

different,” he says. “It was something that I had to find many things

out. It was a good experience.” However, his part-ownership didn’t

entail the former terror of the courts having to endure the embarrassment

of disciplining players who misbehaved: “I was not a director of the

tournament. I was owning the tournament but I didn’t get that deep, being

involved so much. I just put my money in.”

Nastase is still closely involved in tennis development. He is also a

fixture on the seniors circuit, where his clowning makes him a crowd

favorite. Unfortunately, the partnership between him and Connors has

been temporarily shelved: “I’m going into the 55-65 now. Jimmy Connors is

a young man. He’s playing in another group with the young players. I’m

playing with the grandfathers now.”

Looking back on his career, Nastase says he is happy with his record. Those who talk of him concentrating on indulging himself too much and

concentrating on his tennis too little and assume some level of lingering

dissatisfaction on his part are barking up the wrong tree. “If you win 57

tournaments and 51 doubles and [four] Masters and I’ve been number one.

I’m pleased with my results,” he says. “So I have both. I’m not

disappointed with myself.”

|