<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

Wisdom and Oddities from the Early Days of Tennis

by Lawrence Tabak

|

|

When the first books on tennis began appearing late in the 19th century, tennis was still an extremely young game. Major Wingfield had first patented his lawn tennis kit (similar to today's backyard badminton sets) in 1871.

The first big lawn tennis tournament, run as a money-making scheme to help bolster the prospects of a faltering Croquet Club, was held at the All-England Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club in Wimbledon in 1877.

So when James Dwight penned Practical Lawn Tennis in 1893, tennis as a tournament sport was only 16 years old. Little wonder some of the finer points had yet to be worked out. And, while there is some entertainment value in reviewing some of the more glaring misconceptions and coaching myths of the time, more surprising is the depth of insights that early observers had for the game.

On grips

The earliest writers on tennis were quick to grasp (pardon the expression) the importance of the how a player holds the racquet. Interestingly, observers in the first decades of the game seemed much more open-minded than many later experts, who can be quite proscriptive regarding correct grips. One possible explanation is the variety of styles that were evident at this time, when players were often discovering the game without the benefit of experienced coaches or preconceived notions. Adding to this was the relative isolation of players.

Unlike today, it was possible for a pocket of top-notch players to develop in, say Southern California, or Southern France, who seldom, if ever, saw their counterparts.

|

|

This from James Dwight's 1893 book:

One would think that there was a right and a wrong way to hold the

racquet, but this does not appear to be the case. I see it held in many

different ways, and the results is merely a difference in style. The

racquet cannot be held in two different ways and the same stroke be made

in the same way…

On the same subject, Wimbledon champions R.F. and H.L. Doherty wrote On

Lawn Tennis in 1903:

Style was once defined as 'the easiest way of doing a given thing successfully.' Style, in tennis, depends a great deal upon how the racquet is held.

Compare this open-mindedness with Don Budge’s advice in 1948 (Budge on Tennis):

If you have ambitions to make a name for yourself in tennis, I advise you to use the…”Eastern grip.”

Two years later Willliam Tilden was even blunter in his How to Play Better Tennis, stating his preference for Eastern grips, which are correct,” and forbidding the Western grip, “which is obsolete and discarded today by experts.

However, this lack of orthodoxy left many issues open. George Agutter, one of the better known teaching pros of his day, spent an entire chapter in his 1930 Lessons in Tennis debating whether players should hit forehands and backhands using the same or opposite sides of the racquet.

|

|

On Good Form

One of the most perceptive of the early observations, as mentioned above, was the degree to which grips affected stroke patterns. However, this was hardly a barrier for experts who wanted to describe the best approach to striking a ball.

For many years, teachers and writers followed a narrow prescription, which focused on such orthodoxies as closed stances and choreographed footwork.

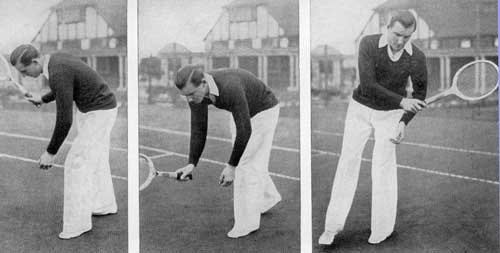

One of the most common snares for these early pundits was the habit of posing tennis strokes in static poses, a boon to the photographer, but almost always a disaster in terms of advice. Even great players seem capable of crippling poses when asked to freeze a particular moment of their famous strokes.

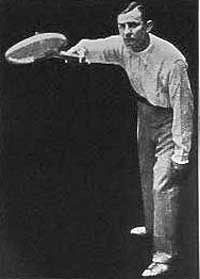

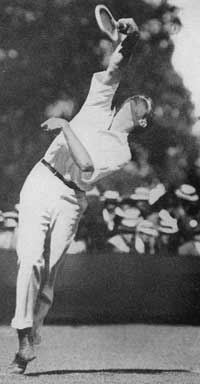

Some of the most egregious examples I’ve found are the self-illustrations provided by P.A. Vaile in a series of books published in the early part of the 20th century. It didn’t take long for the tennis world to take note. In 1907, J.W. Payne published Tennis Topics and Tactics, which is largely devoted to ridiculing Vaile. It should be noted that despite the generally sound objections raised by Payne, he demonstrates his own idiosyncrasies.

In Tennis Topics he devotes the entire first chapter to a polemic on why Great Britain should not abolish its national guard. He ties it in neatly to the book’s main subject in the last paragraph, by insisting that tennis players prove to be superior marksmen.

|

|

|

Vaile Low Backhand Volley with Lift (left) - Although it is unclear how Vaile will impart topspin (lift) on this particular volley, he can’t be criticized for not “getting down" to the ball. The "heroic" forehand finish speaks for itself. |

|

While Vaile’s work does subject itself to broad criticism, he does show admirable frankness. How many modern tennis writers would be forward enough to say, as Mr. Vaile does, on a later edition of his book that It is published also in French and German, and is recognized as the standard work on the subject? Or would have the nerve to promote his own admittedly unconventional tennis garb: I wear knickerbockers—the best garb for tennis—a soft shirt without any starch, and I roll up my sleeves.

But these small merits crumble into sawdust under Payne’s withering criticism. Vaile’s book, Payne notes, was published by a firm of racquet makers whose racquet Mr. Vaile has discovered by a remarkable coincidence to be the best on the market. The outer cover shows Mr. Vaile in the act of serving…which constitutes in the eye of a practical lawn tennis player one of the most comical things in the whole book.

But wait, it gets better: He summarizes the major difference between Vaile’s recommendations and the way the best players hit the ball as “due to the fact that, unlike them, he was untrammeled in producing them by any petty considerations of prudence about keeping the ball in court, but with no other opponent than the photographer, could give free scope to his taste for the picturesque. When a man’s strokes are not hampered by such trivialities as baselines, he can produce some grand and spectacular, though imaginary, finishes.

|

|

On Vaile’s backhand stroke pose: “The ball would simply have disappeared over the tea tent, or some such place to the right at the altitude of about 60 yards.

On Tactics

If you were forced to reduce the essence of tennis tactics to one sentence, it would be difficult to improve upon J.W. Payne’s 1907 pronouncement that “Accurate hard hitting is the foundation of success at tournament tennis.”

Naturally, not everyone was as prescient about the future of power tennis. Mercer Beasley worked as a coach with many of the great American players of the 1930s, including Ellsworth Vines and Frank Parker. He condensed much of his wisdom in How to Play Tennis, written in 1933. The basic principal of tennis is accuracy, and not strength. If it were a matter of hard hitting and brute strength it stands to reason that the heaviest and strongest player would win, while actually quite the reverse is true…the speed of the ball is secondary.

Another major controversy revolved around the use of spin, particularly topspin, which was more commonly referred to as “lift.” Topspin was utilized by the earliest players, but the vision of two modern clay court specialists at the French Open would have left them slack-jawed.

As late as 1930, tennis professional George Agutter was confident in professing; It’s unwise to use a lifting [topspin] stroke as a foundation to your game…A lift stroke travels very high over the net and a good player will put the ball away.

|

|

Payne could not envision how a topspin shot might have advantages over a flat one. It is absolutely incorrect to assert, as Mr. Paret (echoed, as usual by Mr. Vaile) that it is possible to hit a ball harder yet keep it in the court with “lift” than with a plain-face racquet.”

Others were simply clueless about the biomechanics of tennis. James Burns, in How to Play Tennis (1915), gives this suspect advice: To go from a flat shot to topspin, when meeting the ball, one has only to roll his racquet over the ball just after the ball has been met. Of course, he fails to go on to report by what legerdemain spin can be applied to a ball which has already left the strings.

A few writers got caught up on their own personal hobbyhorses. Mercer Beasley was certain that every player in the world would soon be on his or her knees, smashing the ball in lieu of hitting high groundstrokes. The overhead drive [the ‘author’s own invention’] is the coming stroke in tournament tennis. Now and hereafter you will see it widely used by many players of the first rank. (The last player of note to be seen hitting this shot regularly was Cliff Richey in the 1970s.)

On Prose Style

Even when misdirected on tennis fundamentals, some of these early tennis authors regularly served aces in their prose, where modern writers can manage only awkward puff balls. Tennis as I play It, 1915, by the “California Comet” Maurice McLoughlin, who heralded the “big game.”

|

|

There is certainly no royal road to an expert game, and no words of mine can turn your lead into gold by some mysterious alchemy,…As with anything else in life, it is salutary to be perpetually dissatisfied with the class of game you play; but this dissatisfaction should never cause despair, if you are really desirous of climbing to the expert class,…When one has mastered the essentials of the game he should then fall easily and gracefully into the style that comes most naturally to him.

It should be noted that McLoughlin teamed up with Sinclair Lewis, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1930. (This combination makes this book particularly collectible—the asking price is often in the multiple hundreds.)

Or take the opening lines of Racquets, Tennis &

Squash, by Eustace H. Miles, written in 1903.

Conscientious teachers of elementary things are a mystery or even an

abomination to the genius, who does not realize that his own exquisite

skill must possess not only the outward and visible signs, that inimitable

blending of dignity, power, and even gracefulness, but also certain

imitable foundations, even if these latter parts of his play be (as

foundations love to be) least apparently important…To the genius it seems

sufficient that the clock is a clock and can be wound up with one small

key. Why take the works to pieces? Why spoil a beautifully harmonious

unity by describing its mechanism—its spring, and wheel, its pendulum and

escapement? Why? Because we want to find out and to be able to alter the

parts which compel the clock to keep poor time and to work altogether

badly. Otherwise we might for ever gaze at the skilful and unskillful

players side by side, and continue in vain to urge the latter to rise to

the standard of the former.

And least it be said that these early observers of tennis were not tuned

to the sport sciences of nutrition, listen to Payne’s admonition:

More promising reputations have been buried among the plates and knives of the breakfast room and the luncheon tent than anywhere else. Or my personal favorite, Eustace Miles’ encomium for overtraining: A usual remedy for staleness is champagne and a hearty dinner.

Modern Analysis Begins

A number of orthodoxies were adopted by tennis early experts. These include always standing sideways (closed), and always stepping directly into the shot. One of the great advances into tennis biomechanics came from the slow-motion filming of some of the great players of the 1920s. These films were made in 1924 under the auspices of the United States Lawn Tennis Association and form the basis for the analysis provided in J. Parmly Paret’s Mechanics of the Game, published in 1926 as Volume II of the Lawn Tennis Library. Parmly notes in his introduction:

|

|

I have studied the methods of expert lawn tennis players for over thirty years and thought I knew what motions they made in producing their strokes. When I watched these films,…I learned more of the game,…and when I had the opportunity of examining them one frame at a time it was a complete revelation.

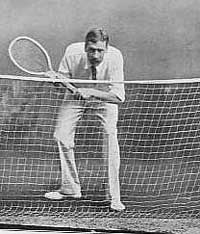

But old theories die hard, and Paret weeded through the slow motion films to find instances of players hitting forehands with straight, rather than bent arms, to support his theory that the further away a player is from the ball at contact, the better. Interesting, the only teaching pro photographed, Agutter, seems at pains (literally) to straighten out his arm before and on contact to demonstrate “correct” forehand form, while the true champions of the era, Bill Johnson and Bill Tilden, look much more relaxed and comfortable.

Other elements Paret noted were deemed only appropriate for championship level players, including their tendency on forehands to use “a round-arm backswing.” Paret insists average players stick with a straight-back swing, and not attempt to master this complex pattern (now used successfully by almost every 12-and-under player in the world).

But despite any faults in analysis, it was clear that

slow-motion photography was a boon to understanding tennis, a process that

has become much more democratic with the availability of digital cameras

and the comparative powers of TennisONE.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think

about Lawrence Tabak's article by emailing

us here at TennisONE.

Lawrence Tabak began teaching tennis in Dubuque, Iowa some 30 years ago and was a club pro in Iowa and California before spending nine years on the staff of the United State Tennis Association. He is currently a Vice President with the Mosaic Mutual Funds in Madison, Wisconsin.

Tabak has written for a wide variety of publications,

including World Tennis, Tennis Week, Tennis Magazine, Racquet, and many

general interest magazines including the inflights for American, United,

and TWA, Fast Company and the Atlantic Monthly.

To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.