<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

The Alexander Technique:

A Way to Effortless, Natural Tennis

by Gary Adelman

This is the first of a series of articles published on TennisONE describing the Alexander Technique, a method of mind-body re-education. The Alexander Technique has been primarily associated with benefiting performance artists, who have found the technique improves their breathing, movement and balance, and hence improves their singing, acting and dancing. The benefits of the Technique have also been recognized by the 20th Century’s most famous philosophers (John Dewey) and writers (Aldous Huxley and George Bernard Shaw).

|

|

That’s nice for actors and singers, you may be saying, but what does this have to do with tennis? Just as actors and singers must learn conscious control of their breathing, movement and balance, so do tennis players.

I

have been a professional tennis instructor for 25 years and a certified

Alexander Technique teacher for 10 years. I have worked with national and

world-ranked players with this technique in Israel and I’ve taught the

Technique to the tennis teams at Harvard, Princeton and Babson College.

This is an overview article on how the Alexander Technique can also be

learned by tennis players to maximize performance and minimize effort and

tension in their game.

The technique was developed by Frederick Matthias Alexander in the late

1800’s. Originally interested in solving his voice problem, F.M.

Alexander, a Shakespearean actor from Australia, evolved a system that not

only solved his vocal problems but revealed the principles of coordinated,

effortless body use exemplified in very young children and in vertebrate

animals.

Afflicted with continuous hoarseness as a speaker and actor, Alexander began to carefully observe himself as he practiced public speaking while standing in front of a full-length mirror. He noticed how he threw his head back and constricted his larynx and breathing. Through meticulous observation, Alexander eventually gained conscious control of his unconscious body habits, resolved his vocalization problems, and was able to resume his acting and speaking career.

|

|

As he taught his technique

to other performing artists, he began to see that breathing and

vocalization were integral parts of how the entire body functions. Over

the next thirty years, Alexander evolved the technique as a means of

gaining conscious control over the mind and body, including movement,

coordinated body use, and breathing. There are now over 6,000 certified

Alexander Technique teachers around the world.

Restoring our natural balance and movement is what the Alexander Technique

is all about. Today’s tennis stars who exemplify this natural balance and

movement include Pete Sampras and Andre Agassi.

Observe Pete’s long-flowing backswing, his smooth, graceful ball toss, the

superb whole body extension and lengthening at contact, the ease and

economy of the motion. Pete Sampras’ serve is an example of a champion who

uses the principles of the Alexander Technique in motion.

Andre Agassi is another example of a player who incorporates aspects of the technique into his game. Observe Andre’s forehand: impeccable balance, the freedom of motion, the uncoiling and up-thrust of his entire body as he lets himself go into his shots, his extraordinary reflexes and timing.

|

Figure 1: Startle pattern |

Figure 2: Poor follow-through |

While the average player doesn’t have the talent of a Sampras or Agassi, the Alexander Technique can help tennis players significantly improve their movement, balance and stroke dynamics. The biggest obstacle to improvement is the habitual ways we use our bodies. In our strokes and movements we have acquired unconscious, automatic habits that make inefficient use of our bodies. The habits referred to here are not the unconstructive, extrinsic habits of which our tennis pro constantly reminds us; i.e., using too much wrist, not watching the ball, incomplete follow-thru or late preparation.

|

|

Instead, the Alexander Technique concerns itself with habits unnoticed and unbeknownst to most tennis teachers. The habits the technique addresses involve those related to misuse of the body and the mind—habits including breath-retention, stiffening the neck and shoulders, shortening and compressing our spines, throwing our heads back, collapsing the chest, pressing down onto our joints, overworking many muscles and under-working appropriate ones.

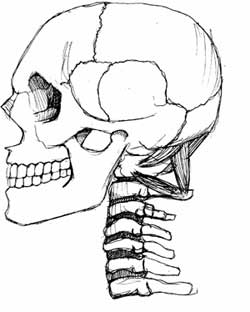

Many players misuse their bodies and unknowingly work against the body’s natural design. Players often use an excess amount of energy to swing a 12-ounce racket while striking a 2-ounce yellow ball. A typical pattern observed in tennis players is called “startle pattern” (see Figure 1).

Identical to the pattern elicited in response to a loud noise, players will react to the sight of the tennis ball by going into a pattern of tension that distributes itself instantaneously throughout their body. Beginning with the stiffening of their neck, their head gets drawn down into their neck. At the same moment they pull their shoulders and their arms up towards their neck, making it virtually impossible for their necks to remain free. They collapse their chests, which restricts their ability to breathe freely. All of this stiffening and extra tension inhibits an adequate follow-thru (see Figure 2) as the player is holding onto himself for dear life.

The startle pattern is only one type of misuse pattern. There are many others. All patterns of misuse have one thing in common. They interfere with a dynamic relationship between the head, neck and back. The use of the head, neck and back in relation to the use of the rest of the body is what F.M. Alexander called the primary control of the use of the self (the self is the body and mind).

|

|

This means the relationship between the head, neck and back governs or controls the coordinated use of the entire organism. Misuse is usually accompanied by excess contraction of neck muscles. Stiff neck muscles disturb the delicate poise and free balance of the head on top of the spine. This leads to a compensatory, chain reaction of stiffening that goes all the way from the head down to the feet. It is the body’s way to maintain balance and prevent the individual from falling over.

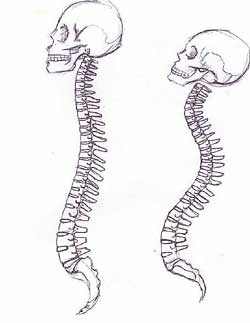

In efficient, optimal use of the body, the dynamic relation between the

head, neck and back is minimally disturbed. Neck muscles remain free

enough to allow the head to balance delicately at the top of the spine. In

Figure 3 the head balances squarely on the top of the spine The forward

predominance of the weight of the head in response to the downward pull of

gravity exerts a traction effect on the spine, causing a lengthening of

the back, spine and entire body.

Figure 4 shows two contrasting head-spine relationships. In the

illustration on the left, this favorable head-spine relation permits a

lengthening of the spine. In the illustration on the right, the head is

tilted back, pressing down on the spinal column, causing excess shortening

and curvature of the spine. This disturbs the balance and flow of movement

throughout the whole body.

The Alexander Technique is a process of unlearning and undoing those

habits and patterns of misuse we have unknowingly learned. It lets the

body work in the way it was designed—naturally. There are no exercises to

learn and no devices to purchase. It uses gravity to produce a whole body

lengthening response against gravity. Players will experience a newly

found lightness and springiness in their movements; more power without

trying; greater ball control and accuracy; smoothness, flow, increased

coordination and timing; conservation of energy; enhanced endurance and a

useful way to prevent injury.

|

|

|

Figure 5: Head-neck-back relationship

allowing free, easy motion. |

Figure 6: Favorable head-neck-back

relationship allows for follow-thru |

In the next article, we will look at how the technique can be applied to on-court mobility. We will explain how movement is initiated and generated in order to increase quickness, improve court coverage, and run effortlessly.

Gary Adelman, a former top player at Columbia University, has been teaching tennis for 25 years and the Alexander Technique for 10 years. Gary is a certified Alexander Technique teacher, having completed a 3-year teacher training program for the Alexander Technique in Cambridge, MA. He has worked with national and world-ranked players with this technique at the Israeli Tennis Center in Ramat Hasharon, Israel, including Anna Pistolesi.

Gary has taught the Alexander Technique to the tennis teams at Harvard, Princeton, and Babson Colleges and will be the assistant varsity women's tennis coach at Princeton University this fall. Gary will also be a presenter at the USPTA National Convention in September in Hollywood, Florida. Gary currently teaches tennis at Canyon Ranch Spa in Lenox, MA. Gary can be reached by email at Garyadelman@earthlink.com. By phone: 413-637-1985.

To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.