|

TennisOne Lessons The Two-Handed Backhand Ray Brown The backhand is a very rich subject. There is the one-handed drive, three two-handed drives, and then there are the spin variations. Clearly, there are too many possibilities to cover in a single chapter of a book, much less in an article. Hence we will only discuss what is common to all backhands and then take a closer look at the two-handed backhand.

As noted in the forehand article, the backhand requires a means of acceleration, a means of stabilization, and a means to assure clean contact between the racquet and ball. As with the forehand, is it beneficial to begin the acceleration phase by pulling the racquet forward by the butt with the but pointing toward the ball. But this is getting ahead of the story. To teach any shot efficiently we must begin with the result we want to achieve and then organize the entire instructional process around that single result. Clearly, in every stroke what we want to achieve is control over direction, spin, and speed. Taking one step backward this requires that we be able to produce clean contact between the ball and racquet. Contact and Extension Achieving clean contact as demonstrated by Bartoli is no simple task. For one thing, each student has a genetically determined set of reflexes and rarely do these reflexes coincide with the actions necessary to produce clean contact. Hence, we as instructors and coaches must recognize these reflexes and design a protocol to replace innate reflexes with precision movements of the racquet to the ball. To do this we must understand all of the variables that can work against this objective. As with all strokes, just before contact, or better, during the contact interval, the racquet must be moving in a straight line along the direction we intend to send the ball. But for a beginner, this step is too advanced. First, one must be able to get the beginner to simply direct the ball back in the same direction it arrived. Even this can be a challenge!

One factor that must be addressed is how the student will use the hands to control the racquet. For the two-handed backhand there are three basic approaches. Left hand dominant, right hand dominate, and equal control from both hands. For the right-handed player, left hand dominant is the preferred choice at our academy, but there are exceptions. In this article we will only discuss left hand dominant for right-handers and vice versa for lefties. Clearly, the video of Bartoli, a 'righty', shows she is left hand dominant. The Rotation Reflex The principle reflex that works against clean contact is the rotation reflex. When the student strikes the ball, there is a natural tendency to move the racquet in a circle rather than a straight line. A good deal of effort must be expended to overcome this reflex. For some students it is a never ending battle. One method we use is to have the student stand still next to the net, place the racquet on the net, and without taking a step, move the racquet along the net in a straight line. We try to impart how this feels physically so the student can distinguish the correct feeling from the feeling of the reflex movement that pulls the racquet off the net.

As noted in the forehand article, when hitting the ball at high speed, the straight line motion must be maintained as long as possible. For the two-handed backhand this is a lot shorter than for the one-handed backhand drive. This part of the discussion suggests tactical maneuvers to force errors. One example is the surprise change of pace that may induce a reflex, thus breaking down the straight-line movement. Another component that can be used to improve extension through the contact region, and thus increase the chances of clean contact, is the shoulder extension. Possibly no one did this better than Andre Agassi. In the video, Agassi's arms seem to be coming out of his shoulder sockets. The result is the addition of several inches of extension length through the contact interval. Further, the left hand dominant two-handed backhand ("left hand dominant" in this context means that the right handed player provides power with the left hand) provides an additional advantage in that it is easier to extend using the left hand than when using other two handed techniques. Acceleration

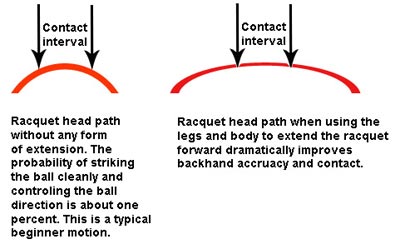

What must happen just before the straight line movement, we call the extension (because one must extend the racquet forward in a straight line to execute this movement), is an acceleration component that is produced by a rotation of the body and arms. This necessary movement often causes serious difficulties in that it not only can be broken down by reflexes, but transitioning from the rotation to the extension is a complicated movement. If this is less than perfect, unforced errors can result. For the beginner, teaching the transition from the rotation to the extension is usually not an option unless the student is gifted. One way to solve this problem is to use the body and legs to extend the racquet motion out toward the ball as seen in the Agassi video on the right On the left, in the figure below is the racquet path for a reflex action or a controlled body rotation. On the right is the racquet path when using the legs and body to extend the racquet path into a straight line.

Note that the contact interval is nearly straight and the probably of an unforced error is greatly reduced. Because the two-handed backhand uses two hands, the rotation reflex is far more troublesome, in fact it is twice as troublesome. Further, the second hand restricts the extension action and, even in the absence of a reflex problem, tends to move the stroke in a circular motion. There are, however, more advanced methods of transitioning from the rotate motion to the extension that do not require a large leg component that will be explained in a later article. Acceleration has another source and that is pulling the racquet forward by the butt (sometimes called the pull and the snap). The longer this component, the higher the final acceleration and thus the final velocity.

In this video, Dinara Safina uses her arms to pull the racquet forward to obtain initial acceleration. Note how the butt of the racquet is pointing at the ball. As her hips turn and stop the racquet face is accelerated forward and the left arm drives the racquet outward toward the ball. She makes a very successful transition from the acceleration phase to the extension phase of the stroke. To obtain this level of initial acceleration, it is necessary to be very flexible. Stability Stability equates to control and consistency. The higher speed or spin one wishes to produce the greater the acceleration needed to achieve that speed and the more unstable the motion becomes. With racquet head speeds approaching nearly 60mph, even a slight uncontrolled wobble in the legs, core, or arm can result in an unforced error. To illustrate an excellent example of stability we refer to the Ivanovic video.

We have inserted a vertical red line through the image to mark her head position during the contact interval. The most important point to observe is how minimal her head movement is during this interval. To have this degree of control of the racquet, one must also have the same degree of control of the body, especially the core and the neck! It is often overlooked that there are tremendous forces being exerted on the neck during the acceleration and contact stages of the stroke. As a result much attention must be given to appropriate conditioning to build up this part of the body. Also observe that the left toe is exerted at contact to provide force on the ball. This is not possible if one uses the cross over step to set up for the backhand. The crossover step is both less stable and less efficient than the open stance backhand. The increase in instability arises from the inability to use the legs and body to produce power as efficiently as with the open stance and hence more reliance on the arms is required. It is less efficient in that it cannot arrest the players momentum and change direction to place the player back into the court as effectively as the open stance.

In general, the more a stroke depends on the arm, the more unstable it becomes. The crossover step's greater dependence on the arms creates the possibility for the racquet face to turn over just before contact thus sending the ball into the net. It also makes it difficult to get the ball crosscourt without creating an unstable motion that could lead to an unforced error. On the other hand, the open stance backhand has its own problems with stability and requires very powerful legs to overcome it. When moving at high speed to the backhand side, the outside leg must be able to single-handedly arrest the momentum of the entire body. This is so difficult that on occasion the outside leg must be used to stop the momentum with a double step on the same leg as Martina Hingis demonstrates in the video above. Summary In summary we see that the two-handed, left hand dominant backhand requires the same three elements as the forehand: Contact, Acceleration, and Stability. While the pull, rotate, transition, extension are the same, how these actions are carried out differs. Unlike the forehand, the two-handed backhand is very limited in how it produces extension. This is problematic and can be used to develop tactics to attack this shot. Particular attention must be paid to the development of the use of the shoulder extension to get a few extra inches of length during the contact interval and to the use of the legs and body to lengthen the contact interval.

We have also demonstrated through careful analysis that conditioning exercises must be developed specifically for the two-handed backhand.This makes it clear that generic conditioning will not be the fastest route to developing a top player. Special leg strength exercises are needed for the open stance shot when running to the backhand side. Also attention must be paid to when the cross over step is used. Players can get into a habit of only using the cross over step because of the fact that it is an easier step to make and requires far less strength in the legs. In some cases special footwork exercises are essential to develop, in the student, the habit of using an open stance backhand. On the bright side, the two-handed backhand promotes the use of the legs and body. This is very significant today with the wide-spread use of light weight racquets which encourage the player to use only the arm and hand to produce racquet head speed. The need to use the legs and body to hit with two hands provides excellent motivation for the player to develop the legs and core. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Ray Brown's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Over the past fifteen years Ray has been working in the area of neuroscience, medical research and brain dynamics while coaching tennis. During this time, he has developed new methods of training that greatly accelerate player development. Ray now operates The EASI Academy in McLean Virginia click here. Ray now operates The EASI Academy ( a unique tennis training center for top high school, college, and professional players) that integrates stroke production, footwork, precision movement, anaerobic conditioning, and mental toughness training in a single program where the student to instructor ratio is 1:1. Ray received his Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of California, Berkeley in the area of nonlinear dynamics and has over 30 years of experience in the analysis of nonlinear systems. He has published over 50 articles on tennis coaching and player development and over 35 scientific papers on complexity, chaos, and nonlinear processes. |

Ray Brown, Ph.D.

Ray Brown, Ph.D.