|

TennisOne Lessons Approach Shots – Depth, Direction and Origin Doug Eng

In Part I, we looked at the most frequently played types of approach shots. Here, we will examine the importance of depth, direction, and origin. The sample consisted of 20 right-handed male players at Wimbledon 2005: Blake, Bracciali, Dent, Federer, Gasquet, Gonzales, Coria, Grosjean, Henman, Hernych, Hewitt, T. Johannsson, Karlovic, Murray, Nalbandian, Philippoussis, Roddick, Safin, Srichaphan, and Tursunov. Directional data would be different if left-handed players were used. It was found that static approach shots were frequently played and as successful as dynamic approach shots. It was also found that classical approach shots including the one-handed backhand slice may be less successful than an overpowering forehand topspin drive. That is not to say one should avoid the backhand slice as it had a winning percentage and under the right circumstances, it may enjoy improved success. Furthermore, club players may have more trouble returning the low slice than touring pros. Finally, dynamic footwork can help club players who need to be closer to the net to play effective volleys.

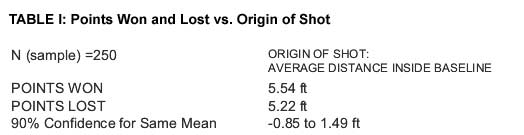

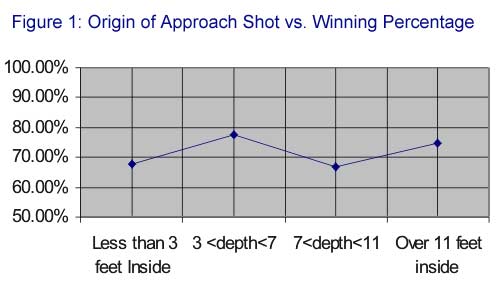

Origin of Shot as a Factor in Success Some 49.6% of approaches in this study were played from the center lane (see court diagram below). The most common shots from the center lane were the dynamic back kick and the static open stance forehands which represented 66.2% of all approaches. Both were equally successful (i.e., ca. 75%). Most dynamic open stance shots were played on the outside deuce (or ad) lanes, especially on shorter balls. This phenomenon is consistent with modern open stance baseline strokes on wide balls facilitating recovery. From the center lane at the baseline, pros often use a square stance. The square stance is also used on approach shots from the center lane but usually with a back kick -- often with a small hop off the front foot -- to promote weight transfer and forward movement. It is reasonable to hypothesize that success of an approach shot increases with closeness to the net permitting easier volleys and reducing time for the defender. Table I shows that on winning points, on average, the approach shot was only 0.32 ft closer to the net than on losing points. Statistically, this difference is insignificant. The 90% confidence interval is from -0.85 ft to 1.49 ft: meaning the winning shots might have averaged 1.49 ft closer to the net than losing points and still be statistically insignificant. The common assumption that one has a better chance on a short ball to approach and win the point is therefore statistically unlikely. The likelihood of winning the point may depend more on other parameters including pace, placement, and quality of volleys. Although the short ball may not be a determinant in the success of an approach and volley point, the short ball may be important for hitting outright winners (as will be seen in an upcoming article). The mentality of hitting outright winners off short balls is quite different from setting up a two-shot approach-and-volley combination. Figure 1 is a plot of origin of the approach shot versus winning percentage. There was no reasonable trend between the origin and point outcome. On the short balls, the winning percentages were fairly high: 75% when 11 ft or more inside the baseline and 66.% from 7 to 11 ft inside the baseline. But on deep balls, including near the baseline, we also see a fairly high winning percentage (e.g., 67.9% winning from 3 feet inside or further back from the baseline).

At, near, or even behind the baseline, a pro can use the “rip and rush” technique discussed in Part I. A pro might rip several shots before sneaking in after a great shot when the opponent is under pressure. Also, the defender may not expect the opponent to rush in and therefore may not hit a low passing shot but rather a higher groundstroke making the volley easier. Therefore, the netrusher has the option of moving forward with the element of surprise or waiting for another opportunity. On the other hand, if a pro simply just rushes in from the baseline on every other ball, he becomes predictable. Also, one must consider that this data was from Wimbledon where the grass courts are considered favorable for closing in to the net, even from the baseline.

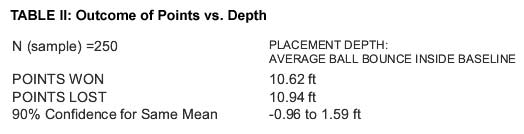

Although the success rate for the “rip and rush technique” is around 75%, waiting for the right rip is not necessarily high percentage. For example, let’s say a player has an average baseline rally of six shots before coming in. Assume there is a 60% chance the rally will end at six hits or less and a 40% chance the player will come in after an average of six hits. If player A has a 50% chance of winning the neutral baseline rally, the player has only a (0.5 x 0.6 + 0.75 x 0.4 =) 60% chance of winning the point. If the player has a 35% chance of winning the neutral baseline rally, he has an overall 49% chance of winning the rally if closing in after six shots. Therefore, in this case, waiting for a short ball is not a winning proposition. The player needs to “rip and rush” earlier than on the sixth shot. Depth as a Factor in Success Depth is considered to be an important factor on an approach shot as it limits the opponent’s reply options and time after the bounce. Depth also gives the netrusher more volley time as the opponent is further away from the net. Table II examines the significance of depth on the approach shot. As seen, there was only a 0.32 ft difference –statistically insignificant -- between points won and lost. The lost points could be have been as much as 1.59 ft shorter (see 90% confidence interval) than the won points without being a significant difference.

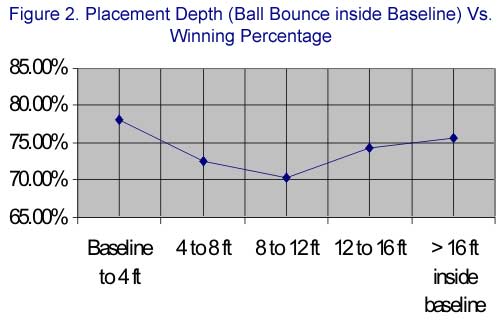

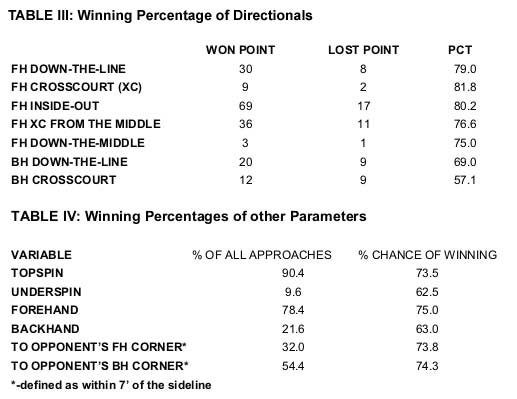

Although Table II suggests that depth is not a significant factor, Figure 2 suggests that there just may be a depth trend that is masked in Table II. The highest success rate was noted for balls close to the baseline (within 4 feet) and balls well inside (over 16 ft from baseline). The lowest winning percentage was for balls that bounced 8 to 12 feet inside the baseline. Statistically, to confirm this trend, more data is required. In addition, other factors – not studied here -- such as ball height and distance from the baseliner may also be important. A reasonably deep approach in the 8-12 feet range does not necessarily move the opponent off the baseline. This makes sense because balls bouncing 8-12 feet inside the baseline are the most comfortable for the defender. It makes sense to suggest that very deep balls and short balls – such as chips -- make passing shots more difficult. Unfortunately, the chip-and-charge tactic is not used much today. In another part of this study, it is suggested that down-the-line slice approach may not have the best success, but if the short chip bounces low and away from the opponent, it may enjoy even higher success. Most baseliners may be vulnerable as they prefer staying at the baseline and hitting with semi- or full western grips. Today’s players, however, may be uncomfortable with the traditional chip-and-charge. It is also worth noting that short topspin balls are often harder to play than short slices or deep topspin drives since the defender will be rushed and may expect the topspin rip to be deep. Direction and Other Parameters The modern approach shot is most frequently played from the middle of the court. The shots from the middle add up to 49.6% of all approaches in this study. The inside-out and crosscourt forehands had the highest winning percentages as seen in Table III. These shots are “high-percentage” shots in terms of using the longest part of the court and opening up the court. One can also argue that the backhand crosscourt also opens up the court particularly if struck wide enough against the two-handed backhand. This shot, however, saw the least success. Most pros can dictate points better off bigger forehands than backhands.

Table IV shows a difference in winning percentages between topspin and underspin and again between the forehand and backhand. The topspin-underspin comparison needs more data as only 9.6% shots were hit with slice. Most approaches were struck to the backhand corner but hitting to the forehand corner had as much success. Altogether, the most successful way to win at the net may be using hard-hit forehand topspin approaches hit equally to either forehand or backhand corners. Closing Notes To further develop this study, different samples could be used to examine the use of underspin, the success rate among female pros, and the success rate on clay and hard courts. Last, recreational players may find success using tactics and approach shots different from what pros use. Strong juniors and college players should emulate the tactics of touring pros. This study is not meant to be the last word on the effectiveness of approach shots, but rather as starting point for discussion. Statistical studies can be limited as to the parameters investigated and change in equipment and player abilities. Ball height, for example, was not examined. However, this research does suggest that traditional tactical theory on approach shots be reexamined. It is also worth suggesting that the underutilized chip-and-charge technique may be highly successful on the tour. The big forehand from the middle of the court directed inside-out to the ad court or crosscourt to the deuce corner is the shot pros most often use successfully. It appears not to matter whether the approach is played moving forward or statically with rotation as a groundstroke. Finally, today’s players are dangerous enough from the baseline as to not wait for the short ball but to make their move off a forcing shot. The modern “rip and rush” tactic is a major weapon in today’s first-strike tennis. We will examine theoretical considerations of classical and modern approach shots including court geometry, court coverage, and changing directions next time. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |