|

TennisOne Lessons Payoffs: Groundstrokes and Directionals, Part II A comparison of Justine Henin-Hardenne and Maria Sharapova Doug Eng EdD, PhD

In part I, we defined the concept of payoff in tennis. We defined it as: % P i = 100 (W i – U i) / N i © Where i=particular stroke technique, W=winners, U=unforced errors, N=total number of (i) played. Let’s call this specific shot payoff meaning we could be looking at a particular stroke (i) such as a drop shot or overhead. We could also define payoff for a particular tactic: for example, points won when coming to the net which might involve a single volley or a couple overheads. Payoffs can measure the effectiveness of a certain shot. A very steady player who makes few winners but a couple more winners than errors can have the same payoff as a player who goes for many winners but makes lots of errors. But a player who made five more winners than errors may have a better payoff than another player also with five more winners than errors. In part I, we looked at the basic payoffs and backhands of Justine Henin-Hardenne and Maria Sharapova. Table I summarizes both players. Do note that there are revisions to Table I in Part I as shown below. The payoffs for Maria on the forehand were lower at +3.7% inside the baseline. Also note the lower percentages for playing inside the baseline. Neither player had a positive overall payoff behind the baseline which shows how difficult it is to win matches playing from behind the baseline. Interestingly, Justine’s backhand payoff from behind the baseline was -4.9% which is actually very solid for a defensive position (as shown in Table 1).

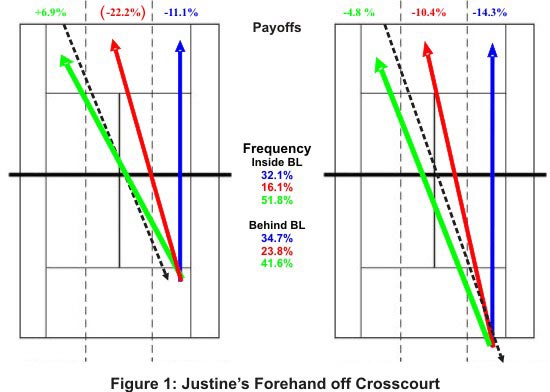

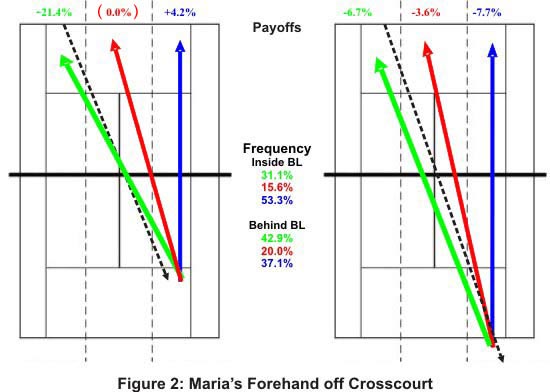

Note that the forehand of Sharapova appears to be bigger than her backhand. She hits winners on nearly 26% of her forehands inside the baseline! But she also misses many of her shots for a +3.7% payoff which is lower than her backhand at +8.9%. Often, we only look at the positive side of things. For example, you might remember best only your winning shots. That could distort your tactical thinking. Remarkably, for both players, the backhand is the better shot with consistently higher payoffs! Note that there is a significant difference for both players whether they are behind the baseline or on or inside the baseline. For example, Justine gains 13.7% payoff when she moves from behind the baseline to in front of the baseline on the forehand. Let’s look at specific trends on the forehands of these two women. So it is critical that Maria tries to take the ball early on the forehand. Figures 1 and 2 show the forehands of Justine and Maria off the crosscourt. For both inside and behind the baseline, Justine’s best play is to not change directions and keep the ball crosscourt (green line). Her shot distribution is not particularly good from behind the baseline as only 41.6% of the shots went crosscourt, her best option. If she could play up to 50-60% crosscourt – as with her shot selection inside the baseline, she might have better results answering the down-the-line. Justine’s +6.9% payoff inside the baseline is partly due to angling the ball away from her opponent. The crosscourts here include both deep and short angled crosscourts, of which the latter is easier to play when inside the baseline.

Maria, on the other hand, played her best going down-the-line when inside the baseline. Maria’s down-the-line was played frequently (53.3%) with a +4.2% payoff. Behind the baseline, her down-the-line was only marginally worse than her crosscourt or neutral through-the-middle shot. A surprising result is Maria’s payoff when she chooses to go crosscourt from inside the baseline which is a poor -21.4% although the subsample (n=14) is small enough to suggest some uncertainty. In the court diagrams (e.g. Figure 1 or 2) if there was some doubt due to small subsampling the payoff value was placed inside parentheses (). It seems that Maria is quite aware of her weakness going crosscourt which she chose a mere 31.1% of the time. In this study, she made 71.4% of crosscourt shots (or 28.6% unforced errors) in this situation. Even when playing the ball neutrally to the middle of the court, Maria hit only 80.4% in which is quite low compared to Justine. We saw Maria’s overall consistency on the forehand from inside the baseline was 78.5%. She is clearly trying to end the point on a winner. Much of her errors are due to her grip and fairly flat, big swing. It’s really hit or miss. Even behind the baseline, Maria changes direction frequently (37.1%) and goes for a lot of big winners which do not appear to get her a great payoff (-8.9% payoff, as shown in Table 1). The moral here is that even a big hitter like Maria can’t win by crushing balls from a few feet behind the baseline.

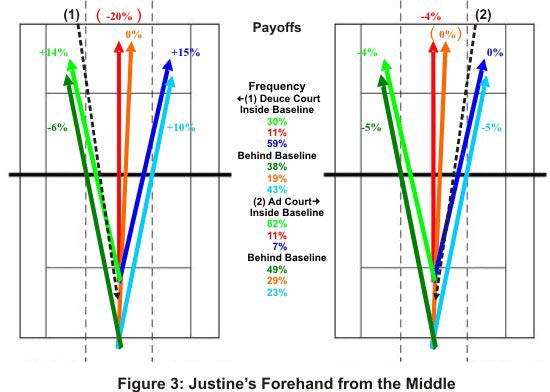

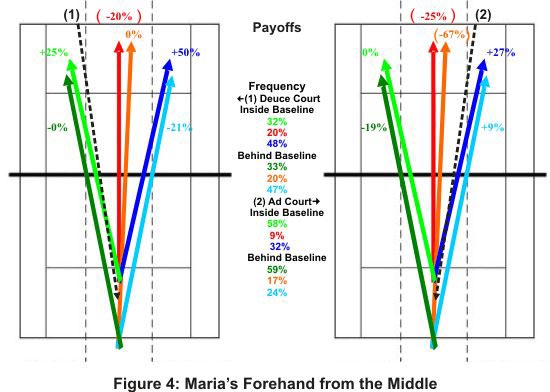

The ability to hit from the middle of the court is shown in Figures 3 and 4. Here we see some unusual results. When her opponent -- all were right-handed -- hit from the ad court (usually a backhand), Justine could not generate any positive payoffs (shown in the right court of Figure 3)! It appears that her opponents could easily neutralize Justine by hitting frequently to the middle when on the defensive in the ad court. In addition, Justine also went predictably 82% of the time with the inside-in change of direction from inside the baseline with a low -4% payoff. Her shot selection appears not good as her other choices such as not changing directions produced 0% payoffs. It is important to note that the other shots were played only 18%, a small statistical sample. Nevertheless, we see some good information using this analysis. Justine’s best pattern was the inside-out off the opponent’s forehand from the deuce court (shown in the left court of Figure 3). In this case, she may a) find the change of the direction easier and b) exploit the backhand weakness of her opponents. Justine had a +15% and +10% payoff from inside and behind the baseline, respectively. As big as Justine’s inside-out is, it is simply not as big as Maria’s. In Figure 4, we see the payoffs for her inside-outs as -21%, +9%, +27%, and +50%. Maria’s biggest shot was the inside-out from inside the baseline (dark blue lines). Like Justine, Maria was relatively ineffective when changing directions to go inside-in (right court, green lines) which I prefer to call the semi-crosscourt. It would be interesting to check other touring pros to see if they also have the same difficulty. For both players, it seems that the inside-out is the easier shot. Even when not changing direction, the inside-outs (blue lines) have higher payoffs than the inside-ins or semi-crosscourts (green lines). Maria’s inside-out is so big, that when she doesn’t change directions, she can still generate a +27% payoff from inside the baseline and a +9% payoff from behind the baseline. As big as her shot is, Maria still shouldn’t run around her backhand to the ad court alley (i.e., the left alley in the court diagrams) as we have seen in Part I.

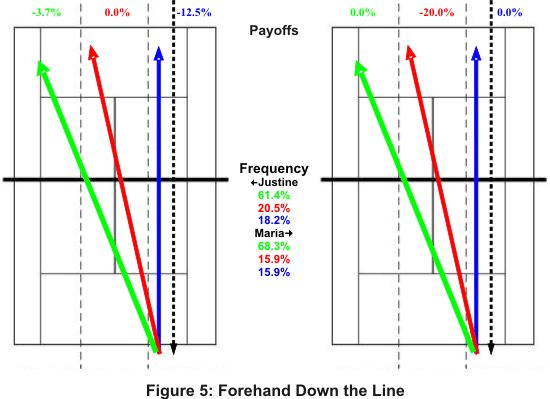

A bit less interesting is the response to the down-the-line as shown in Figure 5. Only the results from behind the baseline are shown since shots inside the baseline are exceedingly rare (24 shots out of 3071 groundstrokes). For the curious, both players struck a forehand crosscourt 75% of the time off a short down-the-line. The combined payoff, as you might expect, was strong at +17%. But in the diagram, from behind the baseline, both players played the crosscourt in the 60-70% range with Maria at a 0.0% payoff and Justine at a -3.7%. Keep in mind that a slight negative payoff in response to the down-the-line is actually not bad. It is similar to having a slightly less than 50% chance of winning a point off your opponent’s serve. Maria actually achieved 0% payoff which means that she totally neutralized her opponent’s down-the-line from the defensive position (behind the baseline). Although we use the expression “neutralize” in reference to Maria, keep in mind she has relatively low consistency on the forehand. Or another way of looking at her forehand, is that it tends to be “hit or miss.” She prefers to dictate the match and win or lose the point off the forehand. So by neutralizing in this case, we actually mean that Maria hits a high but equal number of winners and unforced errors in going crosscourt off the down-the-line. Certainly the other common use of “neutralize” meaning you take the steam out of your opponent’s big shot by usually hitting deep (and often high) doesn’t apply to Maria. Earlier, we also discussed that Maria’s down-the-line (off the crosscourt in Figure 2) is about as good as her crosscourt. In Part I, we found that Maria’s backhand down-the-line was, in fact, superior to her crosscourt. That doesn’t mean she should play mostly down-the-lines, of course, but she should play a relatively high (30-50%) down-the-lines off the backhand. If you recall, Maria seems to be aware of this and does indeed play much more down-the-lines than Justine. In Figure 5, we again see evidence that Maria’s down-the-line may be as good as her crosscourt. The payoff in Figure 5 for the down-the-line is 0.0% or the same as the crosscourt. That is remarkable considering she is behind the baseline and isn’t changing direction but she may be hitting behind her opponent. In short, combined with her inside-out, Maria is very good at breaking down her opponent’s backhand (all opponents for both players were right-handed in this study) since her down-the-line and inside-out forehands have excellent payoffs.

Conclusions In this study, we see the effectiveness of using a combination of statistics to tell us more about tennis tactics than the usual traditional statistics. This information can be used to a) show a player what she can work on or b) be used to scout opponents and develop game plans. It can be a bit cumbersome at the amateur level since you would need to compile data over several matches to generate validity and reliability. Looking at less than 500 shots (or typically 3-4 matches) isn’t enough data since the subsamples for particular shot sequences are small. A large sample as in this study is more reliable and also eliminates specific tactics used against a particular player. However, a player’s tactical trends may change during this period. A parallel example in baseball might be when a player hits .250 in May but hits .350 in September. Baseball statisticians, nevertheless, develop ways to measure how hot or cold a player becomes. Tennis doesn’t use statistics as much as in baseball as many are harder to track. In tennis, certain trends (e.g., big inside-out forehand) usually don’t change that much, but a player may run hot or cold. That is, the player may get better, but still have as a primary weapon, the inside-out.

This study looked at groundstrokes only – just one aspects of tennis. I did not examine spin but the majority of shots were hit with topspin. In addition, I also did not differentiate between deep crosscourts and short angled crosscourts. Directionals is considered an important part of tennis tactics. It is considered more difficult to change direction of the ball and easier to hit back where the ball came from. The area to hit the crosscourt is also larger and the net is lower. That is true, but being consistent may not win you matches. For example, you would not use your second serve as the first serve since your opponent will attack you. What we must generally consider is the risk of what we do. It might be true you can get more balls in going crosscourt and maybe run your opponent more. But if the court is open, should you take the chance to miss in return for a chance to win the point? In addition, it seems that many players are over-anticipating the crosscourt in today’s game. If you saw the recent Baghdatis-Roddick match at the 2006 Australian Open, Andy was caught flat-footed frequently as Marcos boldly struck the down-the-line winners. Even if you hit a tremendous crosscourt, if you hit it 70% of the time or more, you lose the advantage of surprise. Your opponent learns to anticipate and cover your best shot. That is why Roger Federer is so good. He has the ability to throw everything at his opponents who become limited in anticipation. Creativity has its advantages. For a big hitter like Maria, she takes those chances to change directions frequently. We saw a lower consistency than Justine but higher payoffs in certain situations.

Justine, on the other hand, is more of a dirtballer (with her two Roland Garros titles), and is more likely to play the crosscourts and take less risks. In Part I, we saw that Justine probably should take more chances on her backhand especially inside the baseline as her payoffs are terrific. Calculating the chances of going in is only one part of tennis. Tennis has human elements. One must also consider the opponent’s position and tendency as well as properly assessing your risks of hitting a winner or missing the shot. For the club player, if you don’t have the big shot, it is quite simple: you must play for the consistency unless your opponent is very much out of position. For the club player with the big shots: you need to realistically weigh your chances. Many players play hit or miss tennis without realizing what their payoffs are. And lastly, we see for even Justine and Maria, that hitting from behind the baseline rarely has a positive payoff. Even if you hit big from behind the baseline, your opponent will have more time as the ball travels further and slows down. You must learn to take time away from your opponent to get positive payoffs. And finally, you should know what you can do well inside the baseline. Which shots generate positive payoffs for you? Often players hit what feels good and avoid what feels bad rather than reasoning out their tactics. If you play blackjack, you will have better payoffs when hitting on 11 rather than 13, even if it is more exciting to hit on 13. Know your weapons and play them frequently. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||