|

TennisOne Lessons Baseline Tactical Risk Analysis of Top Female Players Doug Eng EdD, PhD In an earlier article, we discussed the paucity of risk analysis of tennis tactics. The easiest and most frequently collected data involve serving and net play. There is very little, however, on one of the largest body of tactics, baseline play. Most of what we consider as baseline tactics is based on theoretical extrapolation using physics and court geometry. In this article, let’s look at some of the best players on the WTA Tour. Previously, we looked closely at the baseline play of Justine Henin-Hardenne and Maria Sharapova. Here, we will expand the study to include Amelie Mauresmo, Kim Clijsters, Serena Williams, and Lindsay Davenport. I chose the WTA Tour players as they depend more on their baseline play than the men on the ATP Tour.

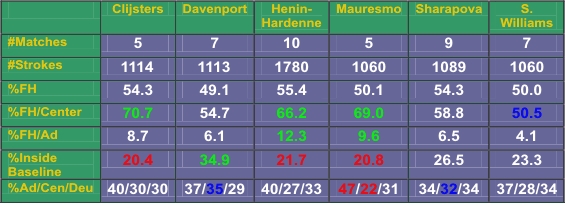

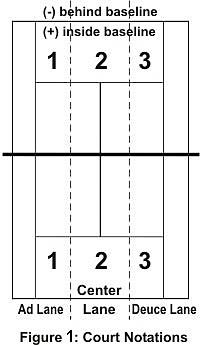

Table I summarizes our six players. All players were right-handed and all matches were played on hard courts against right-handed opponents. Four have two-handed backhands and Mauresmo and Henin-Hardenne are the one-handed backhand players. A minimum of 1,000 groundstrokes for each player was studied. About half of the matches were won to control skewing of data. Table 1: Summary of Baseline Play Favoring the Forehand The data in Table 1 breaks down several tactical variables. One is the ability or willingness to run around the backhand. The players trained on European clay courts -- Clijsters, Mauresmo, and Henin-Hardenne – were far more likely to run around the backhand. The court notations shown in Figure 1 divide the court into three lanes: ad court lane, center lane, and deuce court lane. In Table I, we see (in green) that from the center lane, Clijsters played her forehand 70.7%. Henin-Hardenne and Mauresmo were the most likely to run around the backhand even in the (left) ad court. Justine played the forehand 12.3% and Amelie played the forehand 9.6% of the time in the ad court lane. Also, only these two women had one-handed backhands. Therefore, the claycourt players and one-handed backhanders were more likely to run around the backhand. Serena Williams was the least likely to avoid hitting the backhand as she played 50.5% forehands (blue number) from the center lane. It turns out that this decision is appropriate as Serena’s backhand may be as effective as her forehand.

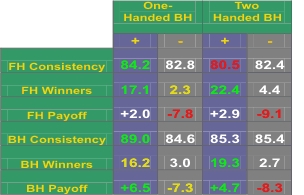

Also shown in Table I are the tendencies of each player to play inside the baseline. This tendency indirectly measures overall aggressiveness and willingness to take the ball on the rise. As you might suspect, the European-trained clay courters (Clijsters, Mauresmo, and Henin-Hardenne) played the fewest balls inside the baseline (numbers in red). The most aggressive player was Lindsay Davenport who played 34.9% of her shots inside the baseline. Maria Sharapova was the next most aggressive at 26.5%. Related to the aggressive play is the breakdown of player position. We often hear that a valuable tactic against big hitters is playing deep to the center lane. It is also more difficult to control play against the biggest hitters, Sharapova and Davenport. In the last row in Table 1, we see that Lindsay and Maria played 35% and 32% of their shots from the center lane. Opponents may be hitting to the center a bit more frequently as not to encourage Lindsay or Maria to hit the big shot angled out of the court. For Davenport , this is actually good news since she is the least mobile of these players and needs to dictate play. On the other hand, Amelie Mauresmo was the least likely to receive a ball in the middle. Rather opponents were able to play 47% of their shots to her backhand or ad court lane. Mauresmo tends to loop her groundstrokes and does not hit as hard as Davenport or Sharapova. Therefore, opponents are not as pressured by her groundstrokes and can move her to her backhand or into the ad court. We will also see later that she is the least likely to hit winners on her groundstrokes. Risk Analysis of Groundstrokes: Payoffs Vs Consistency In an earlier article, we defined the concept of payoff in tennis as % P i = 100 (W i – U i) / N i © where i=particular stroke technique, W=winners, U=unforced errors, N=total number of (i) played. Let’s call this specific shot payoff meaning we could be looking at a particular stroke (i) such as a drop shot or overhead. Payoff measures the effectiveness of a certain shot. A risk-taking player who makes many winners and unforced errors may have the same payoff as a steady player who makes few winners and unforced errors. Table II shows percent consistency and payoffs of the six players. The “+” and “-“ signs at the top of the table refer to whether the shot is played inside (or on) the baseline (+) or behind the baseline (-). Green numbers signify high effectiveness and red numbers signify poor effectiveness. The three areas examined in Table II are consistency, winners and payoffs. Besides payoffs, the percentage of groundstroke that are in the court (consistency) and percentage of groundstrokes that are hit for winners are given.

A quick examination shows that Henin-Hardenne is the only player with no red numbers. That is, she has no poor results. Amelie Mauresmo was extremely consistent as green numbers are shown in both forehand and backhand consistency categories. Mauresmo, however, was not highly effective in terms of hitting winners or achieving high payoffs. As mentioned earlier, she hits fairly loopy strokes rather than driving the ball hard. She takes fewer risks on groundstrokes and is not able to punish the ball like Maria Sharapova. Her tactics may allow opponents to dictate play and she relies more on her opponents’ errors than hitting winners. For Mauresmo to win matches, she must depend more on fitness, serving, and net play. Another result that stands out is Maria Sharapova’s forehand. Her consistency inside and behind the baseline are 78.0% and 80.8%, respectively. Her forehand was the least consistent but not the least effective. Rather she has the ability to hit the most winners as 25.6% of her forehands from inside the baseline were winners. Overall, her effectiveness or payoff is more to the middle of the six players. The most consistent backhand belonged to Henin-Hardenne, closely followed by Mauresmo. This observation is striking as both players are one-handed backhands and many of us often think of two-handed backhands as more steady or effective for female baseliners. The least effective backhand belonged to Kim Clijsters who had a -7.7% payoff inside the baseline. That means, even on a short ball, Kim is more likely to make an error than hit a winner. The biggest game inside the baseline belonged to Lindsay Davenport and Serena Williams. Both were able to hit over 20% winners off both the forehand and backhands inside the baseline. On the other hand, both players can be somewhat inconsistent inside the baseline. For example, Davenport ’s consistency inside the baseline was 82.0% on the forehand and 81.5% on the backhand. Neither statistic is particularly good among these players. Table II: Consistency and Payoff Often we think of short balls as being easier to hit. When you miss a shot, you may wonder how you missed such an easy set-up. But theoretical results show that errors can occur more frequently on shorter balls inside the baseline since: a) timing to hit on the rise is more difficult than hitting when the ball is coming down, b) the ball is moving faster inside the baseline and if you move back, you are often working with a slightly slower ball due to ball-air friction, c) as you move forward, you give yourself less time and a shorter court to work with, and d) many players often try to be too aggressive on shorter balls and increase their chances of making errors as they try to hit harder. Of course, as you take the ball earlier, you also increase the chances of hitting a winner. In fact, in most cases, as you move forward, your chances of hitting a winner increase faster than your chances of making an error. Take Serena Williams, for example, on the forehand. Behind the baseline, she was fairly consistent at 84.7%. But when she moved inside the baseline, her consistency dropped to 78.7%. Although her consistency dropped 6.0%, her winners increased from 4.7% to 23.3%. Her payoff increased from -7.6% to +2.0%. Another example is Davenport’s backhand. Lindsay got 85.4% of her backhands in the court from behind the baseline. When she stepped inside the baseline, she could only keep 81.5% of the balls in the court. But her winners increased from 3.0% to 23.9%. Her payoff increased from -7.5% to +5.9%.

If you apply these results to your game, you should consider that making an error inside the baseline should not discourage you from trying to be aggressive. I see too many players back off from being aggressive if he or she misses a couple approach shots or swinging volleys. They often focus on the few mistakes they made or the few passing shots their opponent made instead of playing the percentages which favors them. Some players become too internalized as they focus on feeling good: e.g., feel like you are hitting well and keep the ball in the court. They forget they are trying to make their opponents uncomfortable and that involves possibly making more errors from their own end. As we see in Table II, none of the players were able to produce overall positive payoffs from behind the baseline on either forehands or backhands. You might ask whether playing behind the baseline loses or not. It depends on your opponent whether he or she is also standing behind the baseline. If you stand behind the baseline, you can surely expect to make more errors than winners (e.g., produce negative payoffs). But if your opponent does the same and makes even more errors, he or she will surely lose. Nevertheless, we can see why it is so important to develop a strong transition game. When you develop an attacking game, you are adding shots or creating court position that allows positive payoffs. Although it is difficult to generate positive payoffs from behind the baseline, it is possible that one or two specific tactics might generate positive payoffs from behind the baseline. We will discuss this later when we look at specific directional tactics. The players who should play behind the baseline the least are Davenport and Clijsters. Lindsay plays the weakest defense of the six players since she is the least mobile of the six and must generate offensive shots to win. From behind the baseline, Lindsay has a forehand payoff of -12.1% (red number) and a backhand payoff of -7.5%. Her forehand is relatively ineffective from behind the baseline. So she can’t really afford to camp back there. And she definitely knows that.

As we saw earlier, Lindsay plays the most frequently inside the baseline (34.9%). If she backed up and played more passively, she probably would not be the dominant player she is. Clijsters is known as a tremendous defensive player but still she actually produces mediocre numbers (in red) with payoffs of -8.9% and -9.1% on the forehand and backhand, respectively. So how does Clijsters win the defensive points? Although her defensive payoffs are not terrific, she does hit a very hard, heavy ball which is difficult for opponents to attack well. We see that strength in her ability to actually hit more forehand winners than errors going down-the-line off the crosscourt. As a player, should you be a consistent player or a risky player? That will largely depend on your temperament, your mechanics, your ability to hit a hard, heavy ball, and your ability to run down balls. For example, a speedy player who uses a western grip will be a consistent player who will succeed on clay courts. A slow, strong player should develop a powerful serve and attacking strokes. That player may use eastern grips and flatter strokes to play what Mary Carillio calls “Big Babe Tennis.” Maria’s and Lindsay’s coach Robert Lansdorf is a proponent of the hard-driving game they both play. But former greats such as an Arantxa Sanchez-Vicario or Amanda Coetzer relied on speed and defense and physically could not develop the big attacking game. Comparison of One-Handed and Two-Handed Backhands In developing young players, it is commonly accepted to start with two-handed backhands (and even forehands for very young students). More junior girls develop and stay with the two-hander whereas boys are more likely to switch later to a one-hander giving promise to a more all-court game. Among the six players, Mauresmo and Henin-Hardenne have the most all-court game. Of course, they have one-handed backhands. But does that make them weaker at the baseline? Table III compares one-handers and two-handers. The two-handers are the four other players: Davenport , Williams, Clijsters, and Sharapova. For the one-handers, I included additional data from the fine Australian player, Alicia Molik. From behind the baseline (numbers in the gray background), the forehand and backhand values were similar. Inside the baseline, the one-handers tended to be more consistent but the two-handers struck more winners. The overall payoffs were very similar but with the one-handers being slightly more successful. For example, on the backhand inside the baseline, the payoffs were +6.5% and +4.7% for one-handers and two-handers, respectively. Behind the baseline, the payoffs were -7.3% and -8.3% for one-handers and two-handers, respectively. One possible answer for the lower number of winners and errors by one-handers might be explained by their tendency to slice more frequently. One-handers are often more selective in trying to rip winners. In any case, we see fairly similar payoffs.

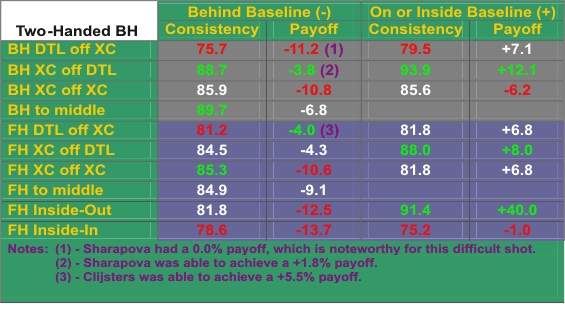

Therefore, although we might think differently, there appears to be very little difference between the effectiveness of one-handed and two-handed backhands. In fact, with these players, the one-handed backhand was slightly more effective. We need to keep in mind that these are among the best backhands in the world and things may be different for a player ranked 300 on the tour or a 4.5 club player. At least at the elite level, the analysis shows that the one-handed backhand can be played at least as successfully as the two-handed backhand. Directionals and Payoffs As the final part of this article, let’s look more closely at the four two-handers in this study. Table IV summarizes a breakdown of percent payoffs on different directional tactics. The most difficult shots were the backhand down-the-line (DTL) off the crosscourt (XC) and the inside-in forehand. You can find the data in red numbers in the first and last rows. Let’s define the forehand inside-in as a run-around the backhand shot taken in the ad court lane that is struck up the left sideline (if you are at the bottom of Figure 1). That is a forehand hit from lane #1 in Figure 1 that crosses the net and stays in lane #1. The forehand inside-out and inside-in Table IV involve change of direction only.

Although the backhand down-the-line was the least successful shot, the most successful shot was the backhand crosscourt off the down-the-line. The three other most successful shots were the forehand crosscourt off the down-the-line, the inside-out forehand, and the backhand to the middle of the court. The forehand behind the baseline poses an interesting case. Although the forehand crosscourt off a crosscourt appears to be the most consistent shot (85.3%), it only produced a payoff of -10.6%. In fact, both the forehand and backhand crosscourt rally from behind the baseline produced poor payoffs. But what other options does one have? If one elects not to rally crosscourt backhand but go down-the-line, the payoff decreases from -10.8% to -11.2% and the consistency drops from 85.9% to 75.7%. But hitting to the middle may be a good option. The forehand crosscourt rally produces lower payoffs than the forehand down-the-line off the crosscourt. The down-the-line is a riskier shot as only 81.2% of the shots were made in the study but the payoffs were noticeable better at -4.0% compared to -10.6%. Today’s big forehands can be threatening even several feet behind the baseline. In addition, some players may fall into crosscourt patterns too readily and over-anticipate or over-cover the crosscourt. Against these players, selectively attacking the backhand with the down-the-line forehand is an arsenal in the modern baseline game. Table IV: Directionals Payoffs For Two-Handed Backhand Players In summary, the cumulative payoffs behind the baseline were all negative. That shows how difficult it is to hit winners from deep in the court. There are, however, some specific tactics where a couple players can generate an extraordinary offense from behind the baseline. These anomalies are shown in the notes to Table IV. In note (3) of Table IV, we see that Kim was able to produce a payoff of +5.5% on the forehand down-the-line in response to the crosscourt. This terrific result is because Kim has a tremendous forehand, is very quick and can set up her big forehand better than most other players. She actually played the down-the-line option 35% of the time which was about the norm for the four two-handers. Perhaps she should consider playing this shot more often. As we also noted before, the down-the-line backhand off the crosscourt from behind the baseline is one of the most difficult shots with a payoff of -11.2%. Maria Sharapova, however, had a 0.0% payoff in this situation (see note 1). Although not a positive payoff, this achievement is quite remarkable considering the difficulty of the shot. Might this be because she plays it more frequently or surprises opponents? It turns out that Maria plays the down-the-line backhand 31% of the time only 4% higher than the group’s response (27%). So there is not much difference and perhaps she should play it more frequently. Finally, in note (2) in Table IV, we see Maria produced a +1.8% payoff on the backhand crosscourt in response to the down-the-line (forehand). She played this shot 69% compared to the group norm of 74%. We therefore see a tendency of Maria to favor the down-the-line more than other players and some terrific payoffs for Maria’s huge backhand. Limitations and Conclusions In any empirical study with humans, results can largely depend on the subjects involved. Different subjects will produce slightly different numbers. In addition, if we take these players’ results against much weaker opponents, their payoffs may be significantly better or skewed. But that doesn’t change the values relative to each other. In other words, a certain player’s payoff inside the baseline should always be higher than her payoff behind the baseline. In addition, players’ games evolve over time and the rate of effectiveness may change from match to match. Therefore, the statistics obtained in this study may be regarded as highly probable but not infallible. Finally, we generalized directions by using three placement lanes. I did not account for exact location, depth, angles, spin and pace. These results may, however, provoke interesting discussions on how we look at tennis tactics. These results do support theory in general:

In addition, we made some surprising observations:

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |

|||||||||||||||

Playing Aggressively Inside the Baseline

Playing Aggressively Inside the Baseline