|

TennisOne Lessons How High Should You Go? Jerôme Inen As was the case with my previous article, "That's the Way the Ball Bounces," about our common knowledge (or actually lack of knowledge) about the bounce of a tennis-ball, I want to start this article with a little quiz.

Suppose you have to set up a ball-machine for practice, and you want the ball to bounce really deep into your court. In other words, you want the ball-machine to shoot a ball from your baseline to the opposite baseline. (Answers are at the bottom of the page).

The correct answers are B. and… (drum-roll, wait for it…): D. To be precise: if you shoot a ball at 50 mph (80 kilometers per hour) and you want it go from your baseline to the other, the minimum height the ball must reach is 15 feet or 5 meters. That is about seven feet, or more than two meters higher than normal height of the back-fence of a tennis court. Don't believe me? Even if you've never gone higher than fourth grade math, you can calculate with me… and see that all earthly laws of nature prove it must be so. Even the most adamant apostles of the idea that ‘tennis is a lifting game,, in my eyes, always under-estimate how much tennis is… well, a lifting game. The Unpopular News All tennis-pro’s can attest to the fact that convincing students that you have to lift the ball over the net to be successful is not a popular lesson. Most beginners have rather macho idea’s about tennis, be it man or women. ‘They believe that pros hit the ball very hard and very low over the net and that's what they try to emulate. This idea about the ‘hard and low’ hitting pro’s is so stubbornly ingrained that tennis-players I know, who sat ringside with me at matches swear that I am wrong. In fact I hear this all the time, "You are wrong. I was there! I saw the way they hit those shots — very low over the net!" So, let’s start with a simple truth. Imagine you have a tennis-ball in your left hand. In your right hand you have a gun that can fire a tennis-ball with the speed of a bullet. The ball will leave the portable ball-gun traveling at 1200 meters per second, which is 4320 kilometers or 2700 miles per hour. You aim the gun, straight. At the same time you drop the ball; from the same height you fire the gun. Which ball will hit the ground first? The answer is, both balls (baring objects standing in the way or interference from air-resistance) will touch the ground at the same time. Say what? This is actually very simple — the speed of an object has no influence what so ever on the gravitational pull of the earth. If it takes 0,45 of a second for a ball to drop from your hand to the ground, it will take roughly 0,45 of a second for the ball shot from the gun to hit the ground regardless of how fast it was traveling Of course the ball shot from the gun will be much further away when it lands. The distance it covered was much larger. There is drag through the air because of the speed. But the time it took to touch mother earth is about the same. Why is this significant? Because with this information we can very simple calculate how high we must aim and at what speed we need to hit the ball to get it from point A. to point B. The gravitational pull of the earth is is 9,8 meters per second, divided by two… then multiplied with the root of the time that it takes for an object to drop to the ground. Now don’t start moaning and rolling your eyes because you want to read about tennis and not about math. Basically you only have to remember the number 4,9… and multiply that two times with the time that a ball merely drops to the ground from the chosen height. Angle of Aim versus Ball-Speed Now it is time for some real fun. We know the net is 0.914 meters (3 feet) high in the center. Suppose we want to hit the ball from our baseline, from a height of 3 feet to the opposite baseline. That’s 23 meters or 75 feet. We now know that it will take the ball about 0,45 of a second to simply drop to the ground from that height. That leaves us with a desired ball-speed of 23 meters per 0,45 second. Which is 51 meters per second. Which means that a ball hit 3 feet off the ground would have to leave our racquet at 184 kilometers per hour. That's(113 mph! That, my friend, is a very tall order. Even Roger Federer would be hard pressed to hit a ball that hard, and let's face it, we ain’t no Roger Federer. And in this calculation there isn't even a correction for wind resistance or spin put on the ball.

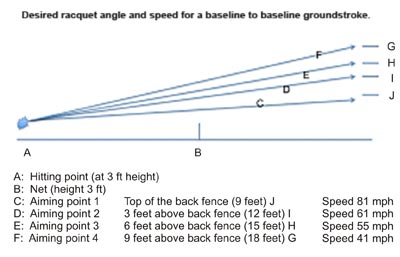

A tennis-ball will leave the racquet at the same angle with which it has hit the strings. The harder we hit, the lower we can aim the ball to get it over the net. But you will be amazed how high this "low" would be. As you can see from the graphic, a ball that is hit at 81 mph — that is about the speed the average male pro’s hit a ball — the angle of aim from a point of 3 feet high should be 9 feet above the desired target. To put it in perspective: that is about the height of the back fence on most tennis courts! If you hit really slowly — about 41 mph — the angle of aim, the strings of the racquet on contact, should point at a place about 18 feet above where we want the ball to land. It is clear that 41 mph is a very slow hit ball, and 81 mph would be very ambitious. So, what would be the best middle ground between the height required and the speed desired? In their article Ball Speed Versus Depth, Ray and Becky Brown described that, though female pro’s can hit balls with speeds up to 75 mph and higher, 60 mph seems about the speed that is sensible… that is their "cruising speed." That has been confirmed by Howard Brody's research, who once calculated that for a ball to fall into the court by the sheer force of gravity, it should be hit about 50 mph. The faster than that you hit the ball, the more topspin you have to add. Male pro’s can manage such high speeds, because they can add so much topspin to the ball. Therefore, about 60 mph seems to be the best cruising speed, a speed that is attainable even for amateur-players.

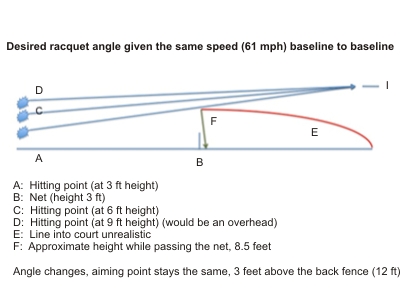

Does that mean we all have to buy a radar-gun and start measuring our ball-speed? For a one-off training, that would be a good idea. But there is a more practical method, and that is using the back fence of the tennis court. The distance between the baseline and the back fence is about 20 feet, which would mean a deviation of about 3 feet in height at the speed of 61 mph per hour. That would not interfere much with what you try to estimate on court. If we align the path of our racquet with a chosen point on the back fence and try to swing with the same speed almost every time, it is not so hard to control the ball. The nice thing is, on top of that, that we can use the same aiming point all the time. As you can see on chart 2, the aiming point stays the same because the drop-rate of the ball stays the same: 4,9 meters (or 16 feet) per second. If we want to hit from baseline to baseline from point A (3 feet high) we aim at point I. If we hit from point C to the other baseline, we also aim at point I. Yes, our contact-point is 3 feet higher…but we also have to aim our racquet-angle 3 feet lower… because we need less extra time for our ball (not) to drop to the ground.

I’ve put a line in the illustration to indicate how line A. would more and less fall to the ground. It is a classical way to portray the desired parabolic lines of a tennis ball through the air. I don’t think it is correct. First of all: the gravitational pull of the earth on a flying ball does not work ‘straight’. The rate of descent gets greater the longer the ball is in flight toward the ground or theoretically until it reaches terminal velocity. For all you physics geeks out there, the terminal velocity of a falling object is the velocity of the object when the sum of the drag force (Fd) and buoyancy equals the downward force of gravity (FG) acting on the object. Since the net force on the object is zero, the object has zero acceleration. Terminal velocity is about 200 mph. But enough of this. So,more the ball exceeds 50 mph, the more topspin you have to add to the ball in order to land it in the court.

If you look at the pictures of Roger Federer practicing with Mardy Fish, you see that the angle of aim is much higher than you would expect. While Federer often hits forehands that are about 3 feet above the net, if pressed (like in this illustration) he will go for the same height as his opponent of this occasion does. For comparison I've put a red line where you can see the difference in height of the ball leaving the frame of the racquet to the ball when it reaches it highest point. And yes, those two balls land in… because of the topspin. My estimation is that the ball at that point is about 9 feet high. I can show probability that by using chart 3 below that shows how much influence topspin has on ball-flight.

We can see from the graphic above that air-interference changes the distance 1 meter (3 feet), while topspin takes almost 2 meters away from the flight distance. What is also important to understand is that it is almost impossible to hit a ball without rotation. If you simply swing from low to high you might not get Nadal-like topspin, but you will get forward rotation and a ball that will start dropping quicker than the gravitational pull of the earth itself would make it drop. How do we apply this knowledge on the tennis-court?

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jerôme Inen's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

"I’ve learned tennis the traditional, form-oriented way — and it is not the right way! Lijftennis is my attempt to show other people a way to learn quicker, with better results and less frustration. If I have one message: don’t copy others, play and learn from your own body and perspective!" |

Jerôme Inen of

Jerôme Inen of