|

Playing the Greats

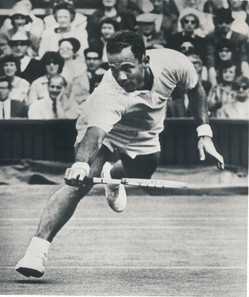

When I was 19 the US Junior Davis Cup team lent a group of promising young players (including Chuck and me) a station wagon in which to tour some of the mid-western clay tournaments. Four of us drove it from Los Angeles to the first tournament in Little Rock, Arkansas, where we met up with the 17-year old McKinley. Right away Chuck began badgering us to let him drive. The rest of us were older than Chuck and knew him well enough to hesitate letting this little barbarian get behind the wheel. Our second evening in town Chuck finally talked his way into the driver’s seat, promptly went speeding down a dark, Little Rock back street, and within three minutes was unable to make a turn and ran the car off the road where it got stuck in the middle of a muddy field. It was a steaming hot summer night and squadrons of mosquitoes swarmed in for a fresh meal. We quickly rolled up the windows (cars were not air-conditioned in those days) and began to smack Chuck on the head for making us choose between sweating to death or being eaten by mosquitoes. Chuck was not without weapons. He retaliated by passing gas and laughing. How could anyone not love a guy like that! Chuck Rarely Hit the Same Shot TwiceOn the tennis court Chuck oozed talent, and he was so powerful that he could whip that old heavy racket around like a toothpick. He had incredibly strong wrists and could hit any shot imaginable. Particularly adept at spins (maybe a holdover from his early days as a table tennis player), Chuck rarely hit the same shot twice in a row. Like virtually all of his contemporaries, he served and volleyed. But unlike them he was likely to hit tricky drop volleys from half court or take the occasional full swing on a high forehand volley. You never knew what shot was coming next. His serve and overhead were strokes of imposing beauty. He was short, but a good jumper, and if he reached a lob it was gone. He hit overheads with shocking force and it was interesting, as a spectator, just to watch him make that ball move so fast.

Most players on the tour are not terribly interested in watching other players play. But watching Chuck was different. He hit the ball so beautifully, so cleanly and so imaginatively we all just liked to see him in action. His tremendous wrists allowed him to impart searing amounts of spin to his serve and the ball took off violently when it hit the court. His action was fluid and quick, and he could hit the flat first serve with ungodly speed. But because he was so short it was a low percentage play for him and he didn’t use it often. He just showed it once in awhile to keep you honest. As you might imagine, little tank that he was,

Chuck threw himself around the court with great speed and abandon. At his

size, he had to be quick. Chuck could really smack the ball and had a big

game for a little man. His most telling weakness was his size and it made

him vulnerable to players like Roy Emerson, who also had a big game but who

was taller, could hit a consistently heavier serve than Chuck, and had

greater reach on the volley and overhead. Still, Chuck was able, on his good

days, to beat just about anybody, and was probably the second best player on

the tour in his prime, after Roy Emerson. Manuel Santana was his equal on

clay but was not as good as Chuck on grass, and Fred Stolle, the other great

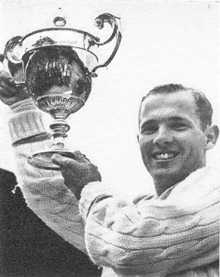

player on the tour, was close, but when they met in the finals of Wimbledon

in 1963 and played for all the marbles, Chuck beat Fred in three straight

sets. Look for Part 2 of Chuck McKinley in the next issue of TennisONE.Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you about think Allen Fox's article on Chuck McKinley by emailing us here at TennisONE.

|

Last Updated 5/15/00. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved. |

|||||

Chuck McKinley burst upon the tennis scene suddenly,

and, like a brilliant fireworks display, lit the sky for a short time and

was gone. Chuck proved it doesn’t take long to get very good at tennis if

you have talent. An exceptional table tennis player, Chuck started to play

tennis at the age of 13 and two years later reached the finals of the

National 15-and-under division at Kalamazoo. The next year, as one of the

best 18-and-under players in the country, he was named to the U.S. Junior

Davis Cup team, and by the age of 17 he was a threat to anyone in the

world.

Chuck McKinley burst upon the tennis scene suddenly,

and, like a brilliant fireworks display, lit the sky for a short time and

was gone. Chuck proved it doesn’t take long to get very good at tennis if

you have talent. An exceptional table tennis player, Chuck started to play

tennis at the age of 13 and two years later reached the finals of the

National 15-and-under division at Kalamazoo. The next year, as one of the

best 18-and-under players in the country, he was named to the U.S. Junior

Davis Cup team, and by the age of 17 he was a threat to anyone in the

world.