<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

The Myth of the Pitch

by John Yandell

ďServing is just like pitching a baseball.Ē Probably everyone who ever took a serving lesson has heard this claim. Itís is one of the most common myths in teaching. Unfortunately, itís not an accurate description. Itís of minimal value in learning to serve and can even be counterproductive. This is especially true if the student has actually played baseball and can throw or pitch well.

|

Actually the baseball pitching analogy is part of a

larger category of misleading analogy myths.

Hitting a one-handed backhand is ďjust likeĒ drawing a sword

out of scabbard. Hitting a forehand volley is ďjust likeĒ throwing a

punch. (See Corky

Cramerís article in the library debunking this myth.)

Then thereís the TennisONE reader, teaching pro, and

correspondent who insists that serving isnít really like throwing a ball

at all. Really, itís just like

throwing a javelin!

There are two related problems with these analogies.

First, rather than simplifying our explanations of the strokes,

they actually make them more complex. What

a tennis serve most resembles isnít a baseball pitch, a javelin throw,

or any other motion from any other sport. The

motion a tennis serve most resembles is a tennis serve!

Why try to hit a serve by emulating a motion from some other sport

that may be bio-mechanically completely different?

Which brings me to the second problem with these analogies. They imply that we canít really understand tennis strokes on their own terms. They have to be compared to other motions so we can learn them. This is not only misleading, it makes tennis seem like a second rate sport. Tennis strokes are among the most beautiful and complex motions in all of sports. They deserve to be understood and taught on their own terms. Imagine a baseball coach trying to tell a pitcher that a fastball is really just like a first serve.

|

To examine the limited and often counterproductive

value of the myth of the pitch, letís compare the delivery of Jason

Schmidt, one of the top pitchers in the National League, to Pete Sampras,

one of the great servers in tennis history. By comparing a major league

pitching motion side by side with Peteís serve, weíll see that the

differences vastly out way the similarities.

(For a more detailed analysis of Peteís serve see

the Advanced Tennis

8 part series on Samprasís motion in the TennisONE library.

Click here to become a member.)

The Obvious Differences

Take a look at the animations of the two motions and

several major differences are obvious. The first and most obvious

difference is that tennis is played by striking the ball with an

implement, that is, a tennis racquet. A

pitcher pitches holding a ball in his bare hand.

Second, the balls are quite different.

In addition to being made with completely different materials, a

baseball is a about one third larger than a tennis ball, weighs more than

twice as much, and has protruding, stitched seems.

A third major difference is the trajectories of the

two balls. With the racquet in his hand, a player of roughly Peteís

height makes contact with the ball about 10Ĺ feet above the court.

A pitcher of the same size releases the ball at a height of about 6Ĺ feet above the ground--about 4 feet

lower than the height of the serve at contact.

|

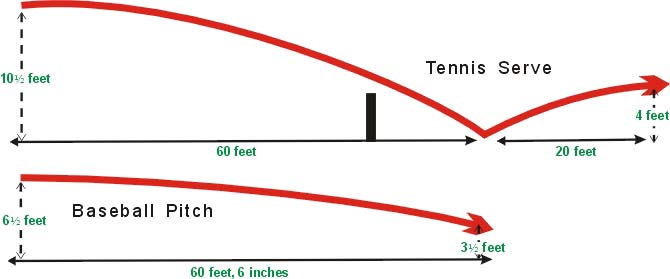

Relative trajectories of a tennis serve and a baseball pitch |

The starting points of the pitch and the serve are therefore quite different. So are the ensuing flight paths. A pitch travels about 60 feet and passes through the strike zone at height of around 3Ĺ feet. It travels on a fairly straight line, dropping at most about 3 feet over itís entire flight. If things go according to plan, it never touches the ground.

|

|

|

|

|

Two characteristics both motions share: the ability to rotate the arm internally backward from the shoulder, and the resulting pronation after the hit or ball release. |

|

The serve on the other hand starts much higher and travels more steeply downward, bouncing at about 60 feet, the same distance at which a pitch crosses the plate. After the bounce, it rebounds to a height of about four feet and travels an additional 20 feet. The total distance the serve travels is around 80 feet, 20 feet more than the path of the baseball.

Unlike the relatively straight flight of the

baseball, the flight path of the tennis ball is in the shape of a double

arc, the first arc from the contact to the bounce, and the second smaller

arc from the bounce to the receiver.

The charts show how different these flight paths really are. Given these differences, it is no wonder that the bio-mechanics are so different as well, as our comparisons of the key positions in the motions will make clear.

Two Points in Common

So letís turn to the bio-mechanics, and compare the

positions of the body at various stages in the two motions.

Letís start by acknowledging the two points that the motions

really do share in common.

First, there is the relatively low level of muscle tension in the body. If you watch the great pitchers, their motions have a silky, relaxed feeling, and this is certainly similar to great servers.

Second, there is one major technical point in common. Servers and pitchers both have significant internal arm rotation and extensive pronation in their deliveries. In fact, the more natural internal arm rotation a player has, the more natural ability to serve or pitch, and the more extreme the pronation.

|

|

Note the differences in the shoulders and the feet. Jason starts basically facing the target zone. Pete begins with the feet and shoulders turned at about 90 degrees. |

|

Pete, for example, can achieve a full racquet drop with his elbow and upper arm almost horizontal or parallel to the court. This is because of his natural ability to rotate the arm backward from the shoulder an ability he shares with most major pitchers including Jason.

Beyond these two points, however, there is little or nothing about the position of their bodies or arms that is the same. The differences vastly outweigh the similarities, as we shall see, and this is why the pitch is such a poor model for developing the serve.

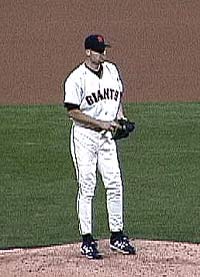

Starting Stance

Letís begin by comparing the starting stances. Pete starts with his torso sideways to the net. His left foot is in front and his right foot is set behind. Jasonís torso is square or parallel to home plate. His feet are also parallel to this same line. And just to repeat the obvious: Pete has a racquet in his dominant hand, not a baseball.

|

|

Pete has his weight coiled primarily on the front leg, while Jasonís front leg is kicking back toward his chest! Note also the angle of the torsos. |

|

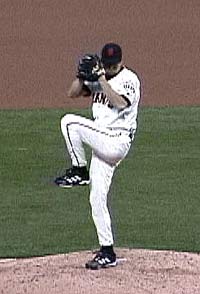

Turn

Note the many obvious differences at the point where both are turned at a maximum away from the batter/receiver. At this point you can see that the analogy between the motions begins to border on the ludicrous.

Peteís torso is inclined, whereas Jasonís is more straight up and down. But look at the legs, and the front leg in particular. Peteís knees are both deeply bent and fully coiled. Most of his weight is on his front foot. Jasonís front leg is in the air practically touching his chest. Obviously, his weight is on his back foot (otherwise he wouldnít be standing!)

Go to page 2

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about John Yandell's article by emailing us here at TennisONE.

|

For more information on John Yandell's Advanced Tennis Research Project, click here.

Last Updated 9/15/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.

Visual

Tennis

Visual

Tennis