<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

Anger and Competition

As a sports psychology consultant, I have

frequently been asked whether some anger in competition is normal, if not

positive. I believe this issue is important and deserves attention.

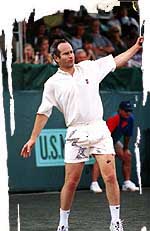

In his prime, McEnroe had an uncanny ability to rechannel anger into a positive force. |

While some anger has proven to actually improve

performance in specific instances, there are many more examples where it

has been destructive. First, let’s examine the origin of anger in match

play and you can decide for yourself what is most beneficial for you.

Typically, anger on the court is caused by a threat

to one’s ego. For example, when a player makes mistakes at critical

times in a match or is losing—the most common sources of anger on the

court—there is an instant recognition of momentary “failure.” That

is, their expectations are mal-aligned with their current reality. This

creates tension and anxiety, which often lead to anger on the court. But

we must be careful not to assume and label this type of reaction as

entirely negative unless we observe a negative impact on a player’s

performance. Often when the anger levels have reached a critical point,

players will either begin over hitting, tanking, or make making more

mistakes, which only fuels the anger pump even further. As the player’s

arousal level rises, fluid strokes with proper biomechanics, effective

strategy, and mental calmness become almost impossible to maintain.

Why, then do we see some athletes actually performing

at even higher levels when it is obvious that they are angry? To answer

this question let’s observe the following scenario.

In most instances, emotional outbursts contaminate a player’s overall quality of play, affecting subsequent points and match results |

Jim is playing somebody whom he knows he can beat.

But in this particular match he is down 4-3 in the first set and, from his

perspective, playing rather poorly. At ad-out, after a long rally, he

misses a relatively easy forehand (his strength) and goes down 5-3. Upon

missing the forehand, Jim becomes incensed. He angrily screams to the

Heavens, “God, c’mon. Let’s go.” But the scream has elements of

extreme competitiveness in it. It has a different quality to it; not

defeated or hopeless, but determined and competitive. Jim is absorbed in

the match, pouring his heart out on every point, and challenging himself.

As you watch Jim play the next point after this outburst you notice that

he plays even more aggressively. You will not hear another outburst from

Jim for quite awhile, probably not until there is another important point

that he badly wants.

However, in most instances, emotional outbursts

actually contaminate a player’s overall quality of play, affecting

subsequent points and match results. In the final analysis, it boils down

to the quality of the anger, which is either fueled by challenge or by

mal-aligned expectations and despair. If it is the ladder of the two, the

problem is no longer a psychological one. It becomes a physical issue.

When players become angry and negative the body responds with a

“flight or fight” response sending a chemical known as cortisol to the

brain, which creates muscle tension. And we all know what muscle tension

does to our strokes.

|

|

The ultimate question you have to ask yourself is

whether your emotional reactions on the court, especially anger, hurts or

helps your performance. If it is hurting your performance then you need to

take steps to improve your reaction on the court. Identifying your

negative self-talk, understanding your beliefs around errors and losing,

and replacing these thoughts and beliefs with more productive ones, will

improve your game. Of course, this takes of honesty and a willingness to

focus on your shortcomings. Make a goal for yourself, to breathe and

re-focus your energy on the next point in a practice match this week.

The best mentality on the court is when players are

so focused and absorbed in competition, having fun, and going for there

shots, that anger becomes highly unlikely because of their involvement in

the flow of their movements. As the pros often (though not always)

demonstrate, errors are a natural part of any match. They don’t become

overly preoccupied with their winning passing shots—unless it is a

critical point—nor do they blow up on their missed opportunities. Their

shots, points, and match results unfold over the course of the match and

they are keenly aware how their composure and reactions impact the

momentum of every match.

When you hit the court take your high energy and competitiveness and channel it into every point. Keep the negative emotions out of the arena. When you get absorbed into the joy of hitting the ball and relishing the opportunity to challenge yourself, you will take your game to a higher level.

TennisONE is an informational and instructional Website. Your feedback is important to us. Let us know what you think and what you’ve learned by emailing us here at TennisONE.

Jeff Greenwald is currently ranked #1 in the world in both singles and doubles in the men’s 35 age division and #1 in the United States in that age division by the International Tennis Federation and the United States Tennis Association respectively.

In 1997, he was the #1 ranked tennis player in Northern California and was named Player of the Year by the USTA. Earlier, Jeff earned a world ranking as a touring professional (he is still ranked on the ATP computer), competing in scores of tournaments on seven continents.

Jeff trained as a youth with John Austin and the late Tim Gullikson. He continues to compete in professional tennis tournaments worldwide, employing and testing the techniques and behavior patterns he teaches in classrooms, boardrooms, and on the playing fields.

Jeff holds a Master's Degree in Clinical and Sports Psychology, is a USPTA certified tennis professional, and is a member of the National Speakers Association.

Readers are encouraged to email their thoughts to the author at jgedge@attglobal.net.

Last Updated 4/15/00. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.