|

Features

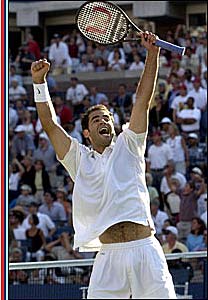

It just goes to show you how psychological a match can be. The underlying psychodynamics of a player can literally shape the course of a match. These dynamics can be very subtle and often are present before a match even begins. They can transcend the naked eye and remain unrecognized by tennis experts on TV who usually tend to view a match in more technical, tactical, and physical terms. Although they often drop a psycho-cliche' here and there, the vast majority of experts are essentially unaware of the subliminal psychological dynamics of a match. This does not mean that I think I am a genius by hitting on a prediction. Instead, my pre-match analysis highlights the need to study psychology on many levels to get the most out of sport psychology as an analytic and performance enhancement tool. The MatchIf you watched the Sampras/Rafter match on TV or live on site you had to be surprised by Sampras' gutteral cry of "YES" when he broke to go up 2-1 in the second set. Contrary to the "body language" or "what you see is what you get" myth (see 8 Greatest Myths of Tennis Psychology article), Sampras' cry conveyed the incredible emotion and motivation he brought into this match. His outcry showed that this generally emotionless, calm, and stoic player had a burning desire to win today, a state he had not exhibited all year. Sampras' desire was based on the emotional memories I referred to in my previous column. These brought his intensity and motor ability to levels we have not seen for over a year. You can't train or merely tell a player to rise to the occasion like

Sampras did. Telling a player like Sampras to get pumped up is not going

to do it. It has to come from within. Sincere and genuine em

Rafter, as predicted, could not get going initially. He was underactivated, slow on his feet, and generally incapable of playing his best early in the match. Mary Carillo intimated that Rafter might be injured after he went through a series of stretching exercises on the baseline prior to a few points. I tend to think he only tightened up briefly early in the match. Rafter probably experienced symptoms and pain of a psychological origin. His psychosomatic reaction to the stress of the occasion limited his mobility, leading to an early deficit that could not be made up. Athletes, like persons in clinical contexts, have a so-called "window of vulnerability" when faced with threats to their comfort or even survival. In Rafter's case, facing an on-fire Sampras threatened his tennis survival and tightened him up just enough to restrict his mobility. In the end that cost him the match. What Could Have Been Done?Knowing the psychodynamics of a player prior to a match is crucial to intervening properly and not just arbitrarily or routinely. Unfortunately, sport psychology, as it is practiced today, is generally reactive and not proactive. Too much attention is paid to the obvious and too little to individual differences, pre-competitive psychophysiological states, and ways of manipulating an athlete's mind-body inter-connections before competition. In Rafter's case, based on his history with Sampras, I predicted he would come out slow and be at a psychological disadvantage. Although he tried to fight his way out of his predicament, in the end it was too little too late. His only chance was that Sampras would roll over and that was not about to happen in this match.

Suspecting Rafter was vulnerable on this day, I would have done a pre-match psychophysiological assessment to determine baseline levels of various physiological systems including heart and brain activity, muscle tension, and temperature and skin conductance levels. Assuming I had been monitoring Rafter over a few months or so I could have readily established a pre-competitive activation and stress state profile and compared it to profiles obtained on days in which he played optimally. Prior to today's match I am virtually certain Rafter would have been shown to be underactivated and over-reactive to stress. If this were indeed the case, I would have used biofeedback, active-alert hypnosis, and cognitive strategies to manipulate Rafter's psychophysiology in the desired direction. Doing so would have counteracted his basic--and, for this day, "natural"--tendency to be both underactivated and nervous. For example, relaxation in a pre-match situation can negatively carry over into a match, preventing players from mobilizing their physical resources (motor or stroke and movement patterns). As a result they then become nervous in situations that otherwise would not have caused excessive stress. Being underactivated leads to the "feeling" one is not playing at a peak level. This reduces one's confidence and can lead to nervousness and poor play. A pre-emptive and proactive approach to sport psychological assessment and interventions is the key to actually impacting psychological performance in the same manner a fitness trainer or coach influences physical and technical/tactical performances of tennis players. This would at least insure that the psychological underdog like Rafter on this day need not be helpless and fall victim to negative psychological influences and factors. Such an approach would go along way to controlling a player's psychological game.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you about think this article by emailing us here at TennisONE. Dr. Roland A. Carlstedt has followed the professional

tennis tours since 1985, fulltime from 1989-1998 in which he on average

attended 25 tournaments a year including all Grand Slam events and

important Davis Cup ties. During this time he complied perhaps the most

extensive database in existence on the psychological performance,

tendencies, and profiles of most ATP and WTA players. His annual

Psychological World Rankings for Tennis have been published since 1991

more than 500 times in over 40 countries. His rankings and data are based

on his Psychological Observation System for Tennis. Interestingly his 2000

rankings which were released prior to the 2001 Australian Open had 2 of 4

semifinalists and 8 of 16 quarterfinalists on them including such unlikely

players as Arnaud Clement and Sebastian Grossjean. His 2001 rankings will

appear in TennisONE at the end of the year.

|

Last Updated 9/3/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved. |

|||||||